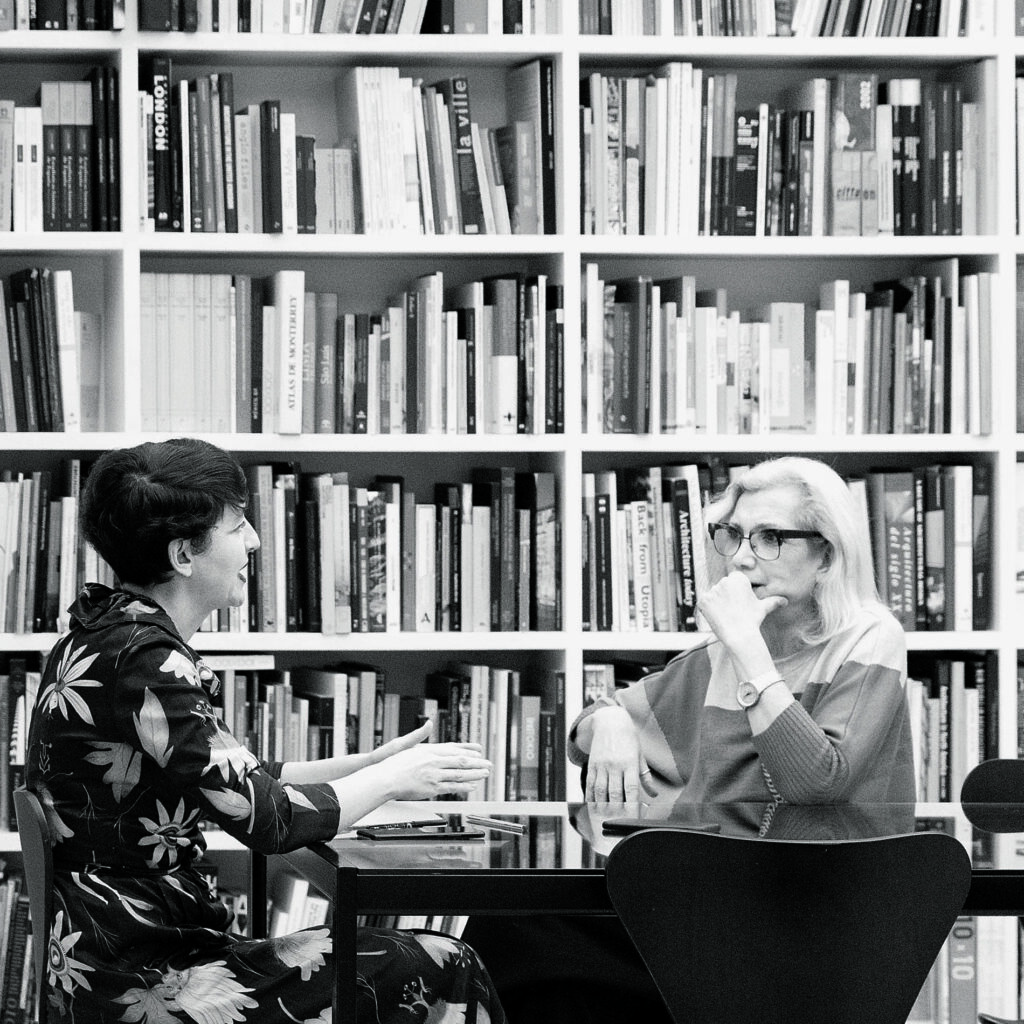

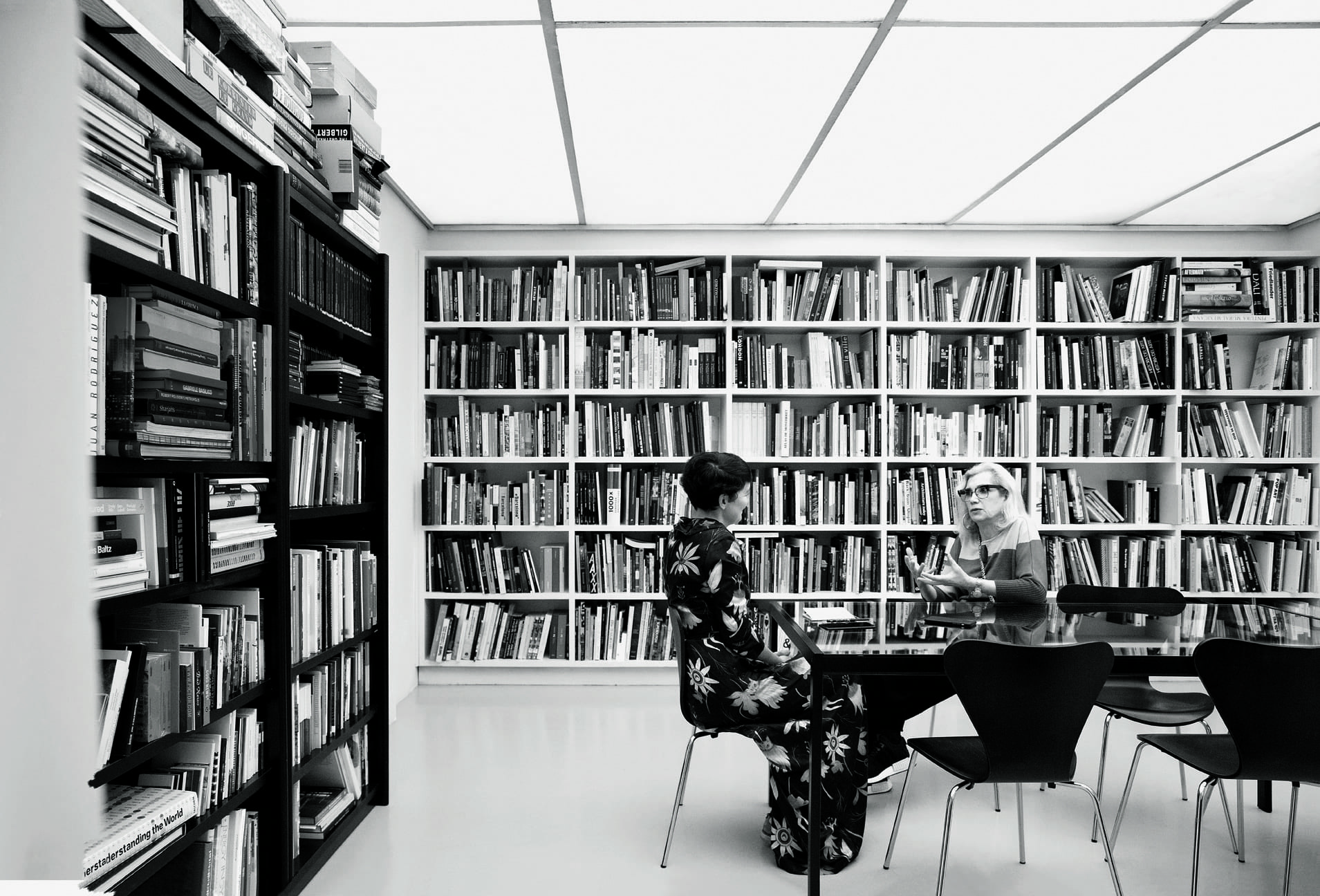

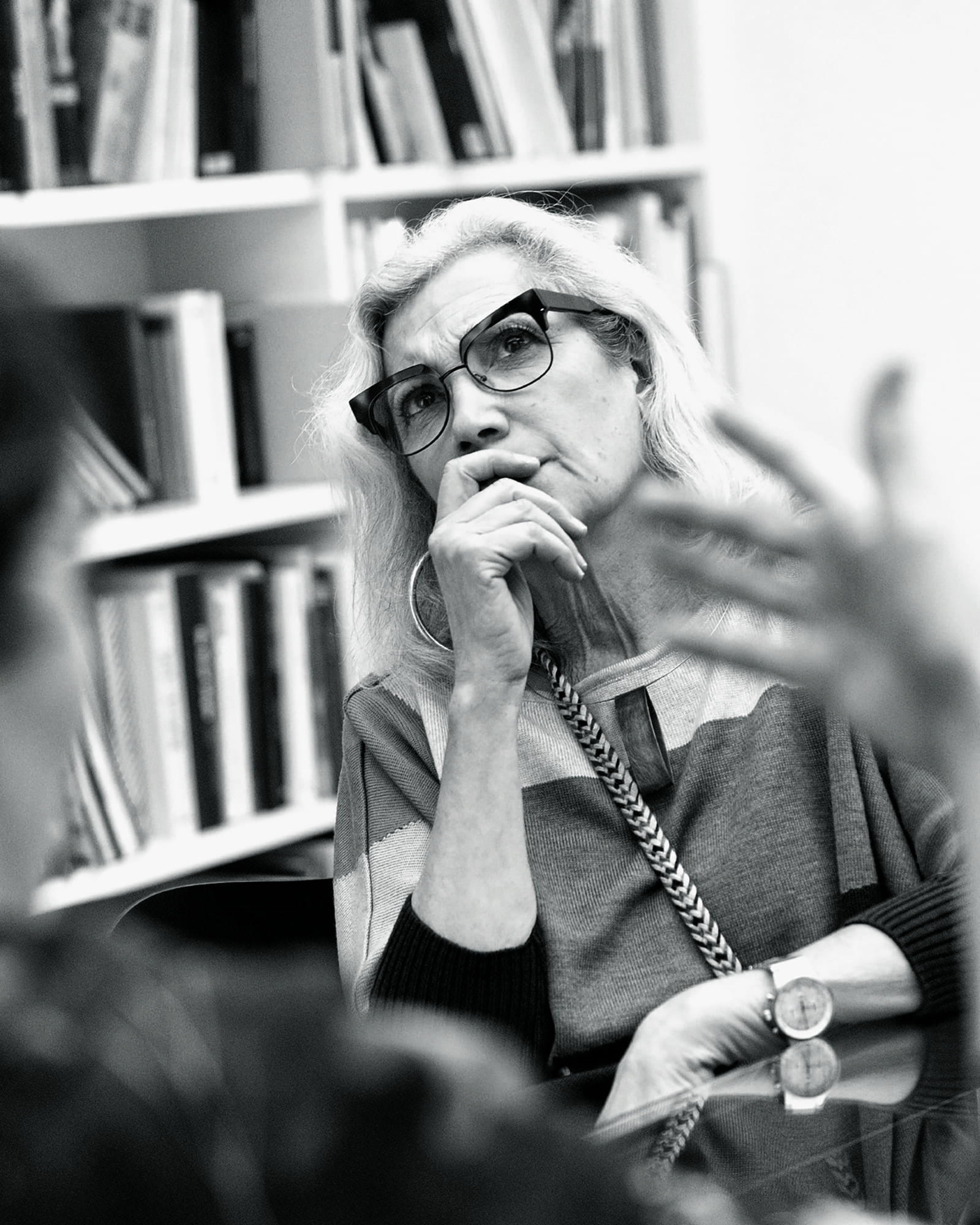

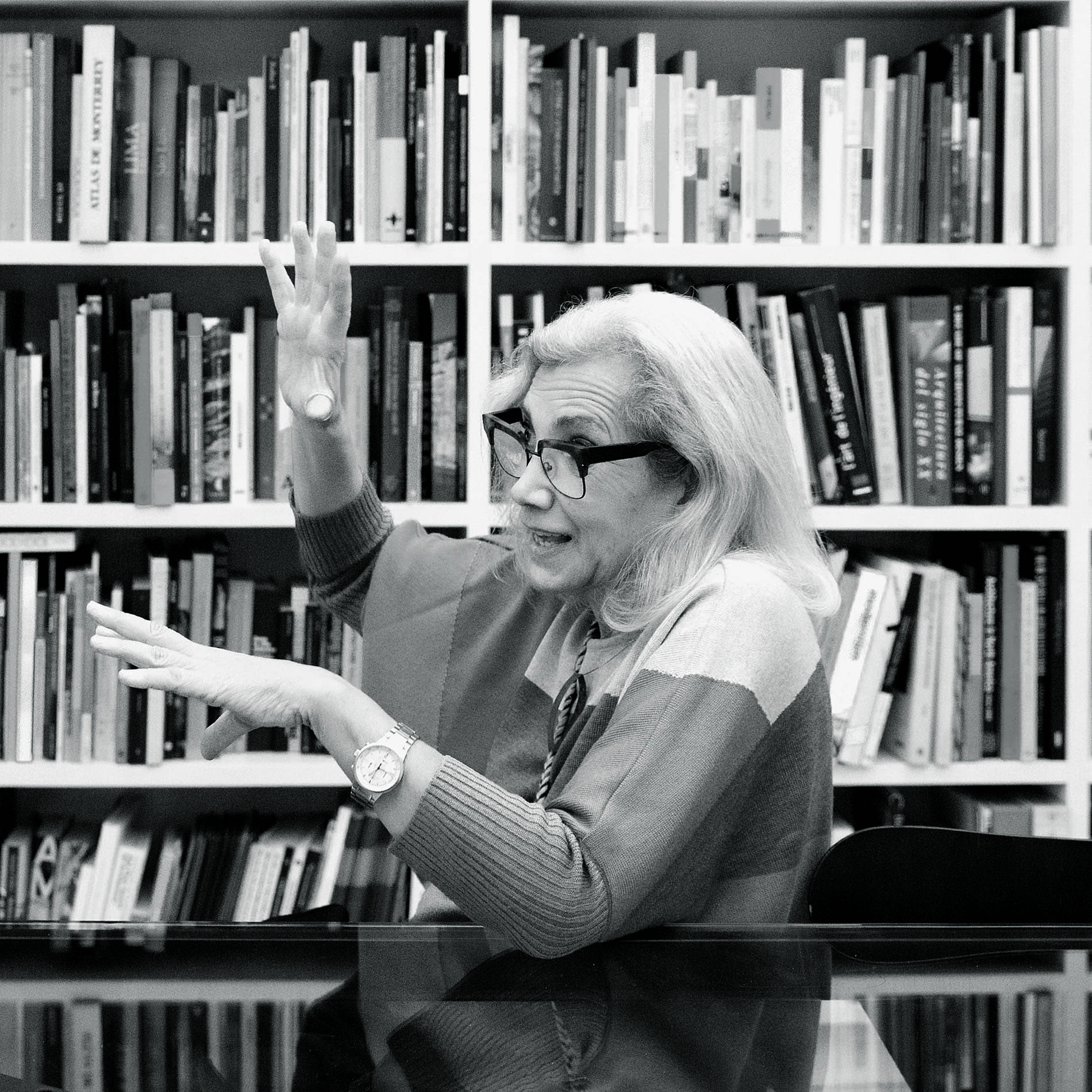

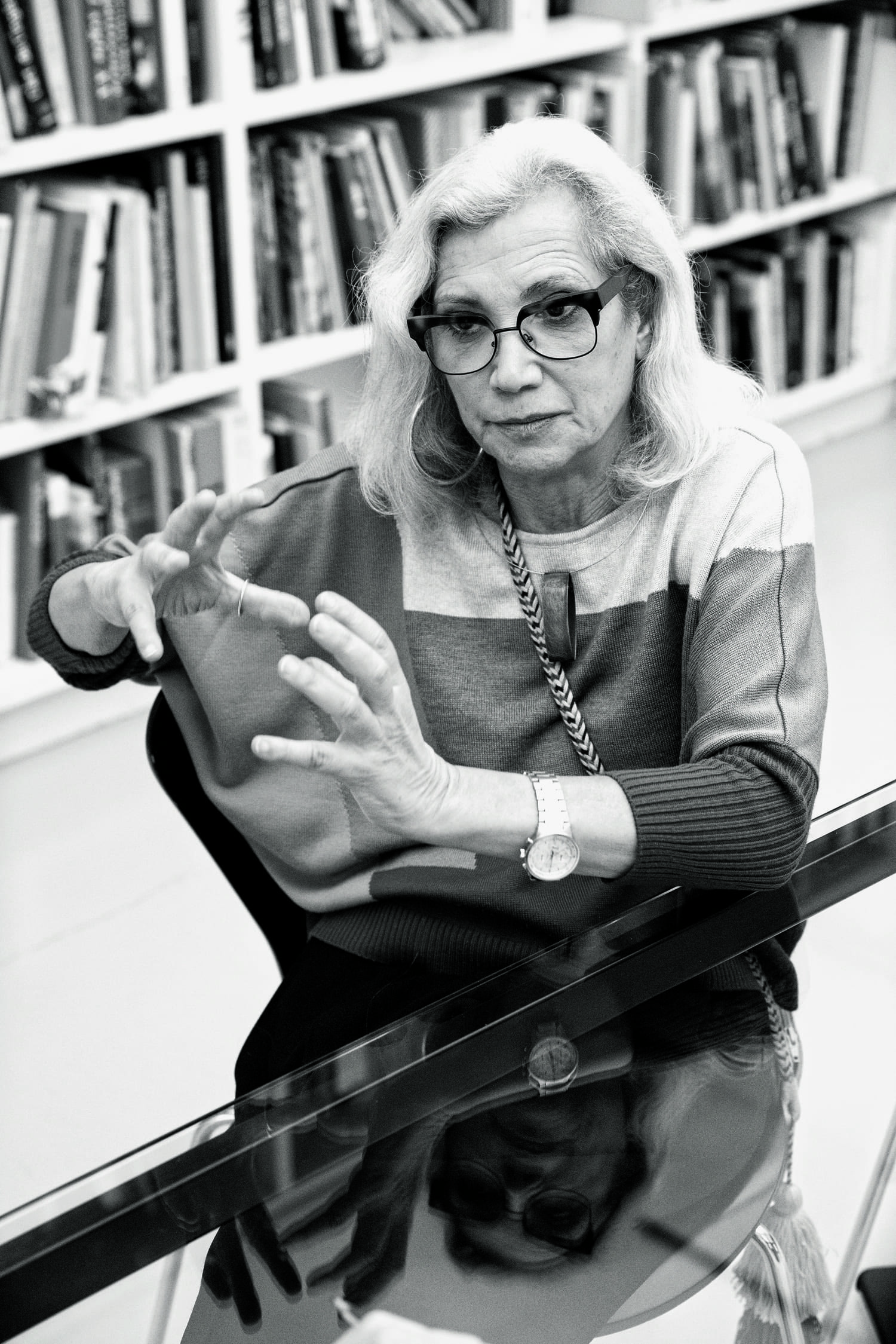

Von Vegesack & Schwartz-Clauss

Von Vegesack & Schwartz-Clauss

In dialogue

Various

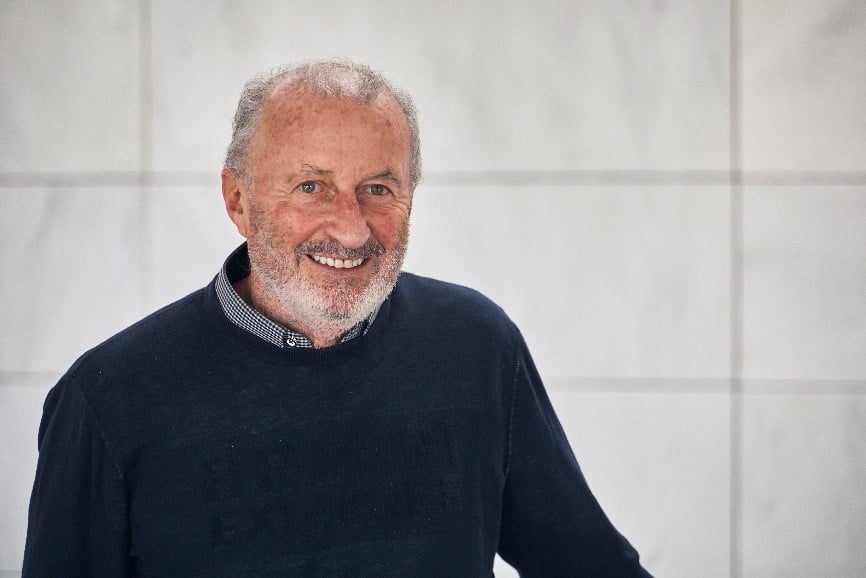

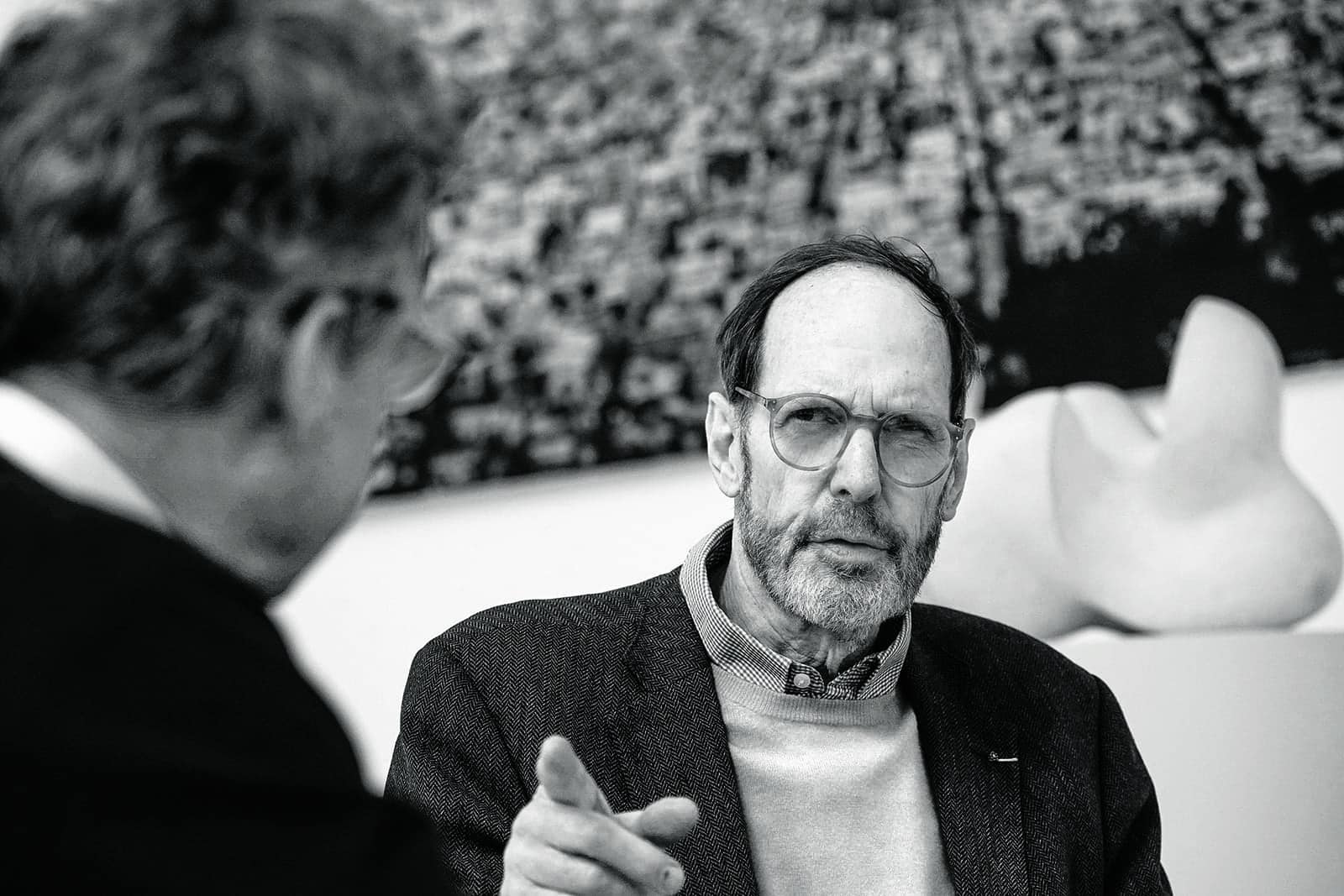

The Domaine de Boisbuchet founder, Alexander von Vegesack, and its director, Mathias Schwartz-Clauss, sit down for a conversation at the Norman Foster Foundation in Madrid.

Alexander von Vegesack never thought to go in for design, but he was a collector from early on. He founded the Vitra Design Museum, and worked with Vitra for much of his career. His life, marked by a postwar German childhood, was always bound to the values of living and working together, so it is not surprising to see them crystallized in Domaine de Boisbuchet: a castle in the southwest of France that each year gathers artists, designers, and

architects in multidisciplinary workshops. Internationally renowned not only for the attendees, but also for the caliber of the lecturers, these workshops are only part of an experience that involves close cohabitation and intimate engagement with nature. Mathias Schwartz-Clauss has directed the workshops since 2013, and in the following interview helps us trace the origins of this ambitious project.

Mathias Schwartz-Clauss: I would like to begin the conversation with the future instead of with the past. Do you worry about your legacy? About what will happen to Boisbuchet in ten or twenty years? And are you happy with what we have achieved so far?

Alexander von Vegesack: I think neither of the past nor of the future, I prefer to think of the present. I’m very much interested in what I can do now to secure Boisbuchet’s future. But its future development will be taken care of by younger people, like yourself, and others following up, and will keep changing, the only constant in life is change.

MSC: Alright, but if you look to the future and simultaneously to the past, back to your childhood, what would you say were the most important steps that led to this project? I feel that it would be a kind of summary of your work.

AVV: I was always very curious, and indignant when people would not allow me to follow my curiosity, so I learned to pursue my interests, and although in this I was not always successful (mainly for economic reasons), I learned an enormous amount from the different activities I did, and exposed myself to many experiences, for which people then appraised me. But if we focus on the period of the Vitra Design Museum, I would say that it was from my period in Hamburg that I really learned a lot. We organized a theater and many social experiments that would be of great help in my first Vitra exhibitions. So I would say that this ongoing curiosity has been the red thread of my life, and that the experiences derived from it are the foundation of what we are doing today.

“Ongoing curiosity has been the red thread of my life, and is the foundation of what we are doing today”

MSC: It’s interesting that you mention the social experiments, and it seems to me that the way you lived and worked in the Hamburg factory became an important part of how we do things at Boisbuchet, which gradually became a community.

AVV: In my view, community was the small family in the beginning, and continued when I was in boarding school. Sixteen people in the same room doing everything together created a system I relate to even today. All the projects that came my way were done with friends, living together, working together, taking risks together…

MSC: At some point in your childhood you also began to take an interest in objects. At that time, these were not objects of ‘design,’ the word ‘design’ did not exist in your world, so how would you say this admiration for objects came about?

AVV: I was born in the last two months of the war and we were living in Düsseldorf, surrounded by houses in ruins. Like all children, we liked to go through the ruins to see if we could find something, like gold diggers. Once we found mosaic in what had been a church. I didn’t know about mosaic floors, but was fascinated by those small pieces. It was part of the curiosity that has stayed with me all my life.

MSC: Düsseldorf is an example of your work, in general, which is ultimately the telling of a story through an object, contextualizing it to create a bigger picture. Sometimes you invent part of the narrative to create a new reality for these things.

AVV: That’s true, but I haven’t finished: years later, it was in flea markets that I continued my search for objects. You could find just about anything, and most interesting were the stories people told about them. You might come across an identical object 50 meters further down the alley, and the dealer would tell you quite a different spiel. I continued doing this in the Netherlands and later in France… and always tried to learn something not just about the object, but also about the people, who they were and how they tried to go about their business. They often made up stories, but there was always some truth to them. I think that part of it rubbed off on me.

But the serious collecting started with the Thonet pieces, when we needed furniture for the theater. I remember finding a lot of pieces, some damaged, some broken… but we would use spare parts to complete and repair others. One day a guy came by and told me about the technology of the chairs, and I was fascinated. So much so that I traveled to Czechoslovakia to visit factory places and learn more. In those days it was strictly forbidden to go into the factories if you were a foreigner, as there was a lot of industrial espionage going on, but eventually I managed to get in, and found lots of catalogs and information. To cut a long story short, this led me to do several exhibitions, many of them in the United States. During one of my trips there I read that William Wyler had died, and I thought it was Billy Wilder. I knew that the film director Billy Wilder had a large collection of pieces of bent wood, so I contacted his family to see if I could buy some.

“I always tried to learn not just about the object, but also about the people behind it”

MSC: So you called the family.

AVV: Exactly. I called and the man who answered was very astonished. I expressed my condolences and proceeded to explain who I was and what I wanted, but he interrupted me saying he was Billy Wilder and that, no, he wasn’t dead. He asked if I had paper and a pencil to write with, and gave me an address. That’s how we met, and we became good friends. One of the first things he did was introduce me to Ray Eames, who was a big help in the beginnings of Boisbuchet because, among many other things, it was she who put me in touch with Rolf Fehlbaum, Vitra’s director, with whom I would work for many years.

MSC: I remember that at the time we met you were working in the creation of the Vitra Design Museum, and I – aspiring to help out in the project as an intern without knowing a thing about design – was fascinated by the passion with which you spoke not only about the future Vitra project, but also about Boisbuchet, which then was just a bunch of farming sheds. But at what point exactly did you, an expert in creating collections for museums and organizing exhibitions, decide to shift your focus to workshops?

AVV: It’s closely connected to my origins. I had always wanted to keep up the groupwork I had started in Hamburg, and I wanted to share the experience, an experience which gave form to my life, with others, so that many more people could live it too. So here, again, we link the past to the future.