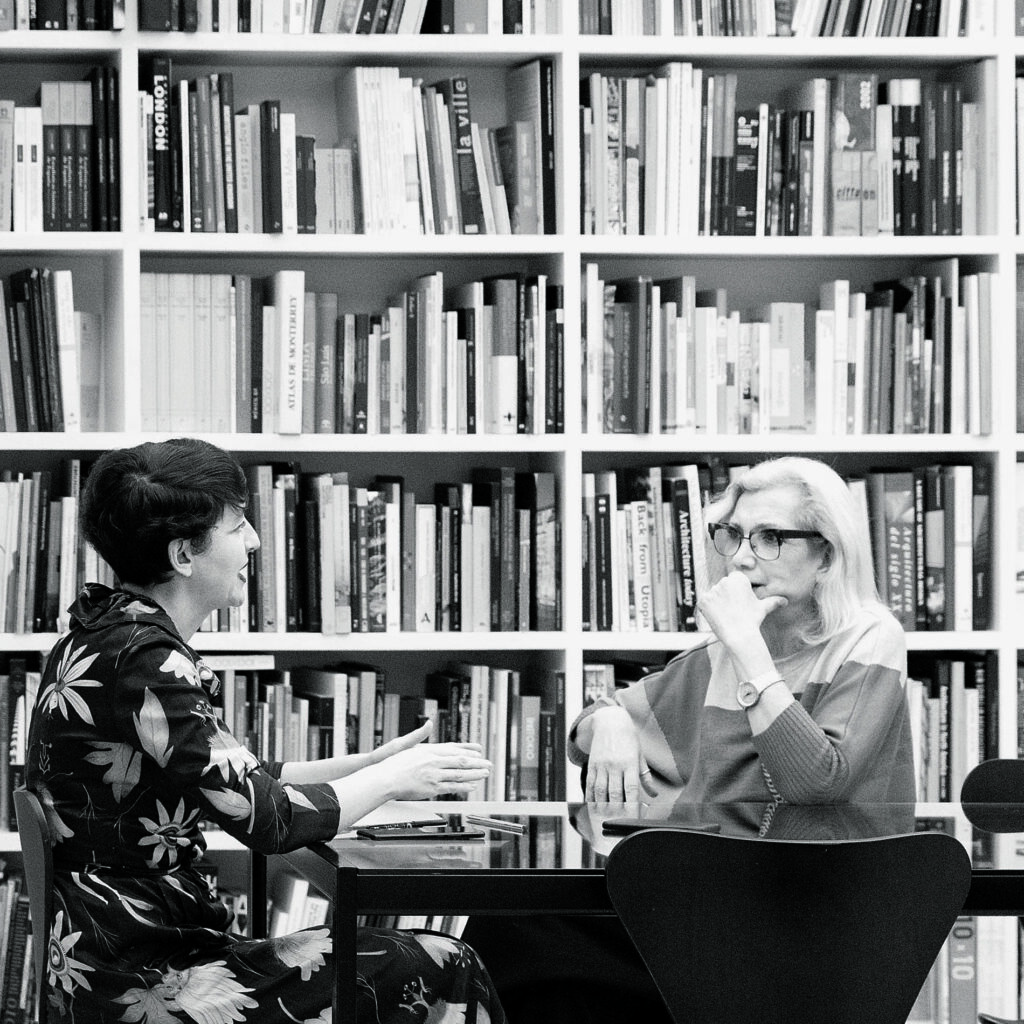

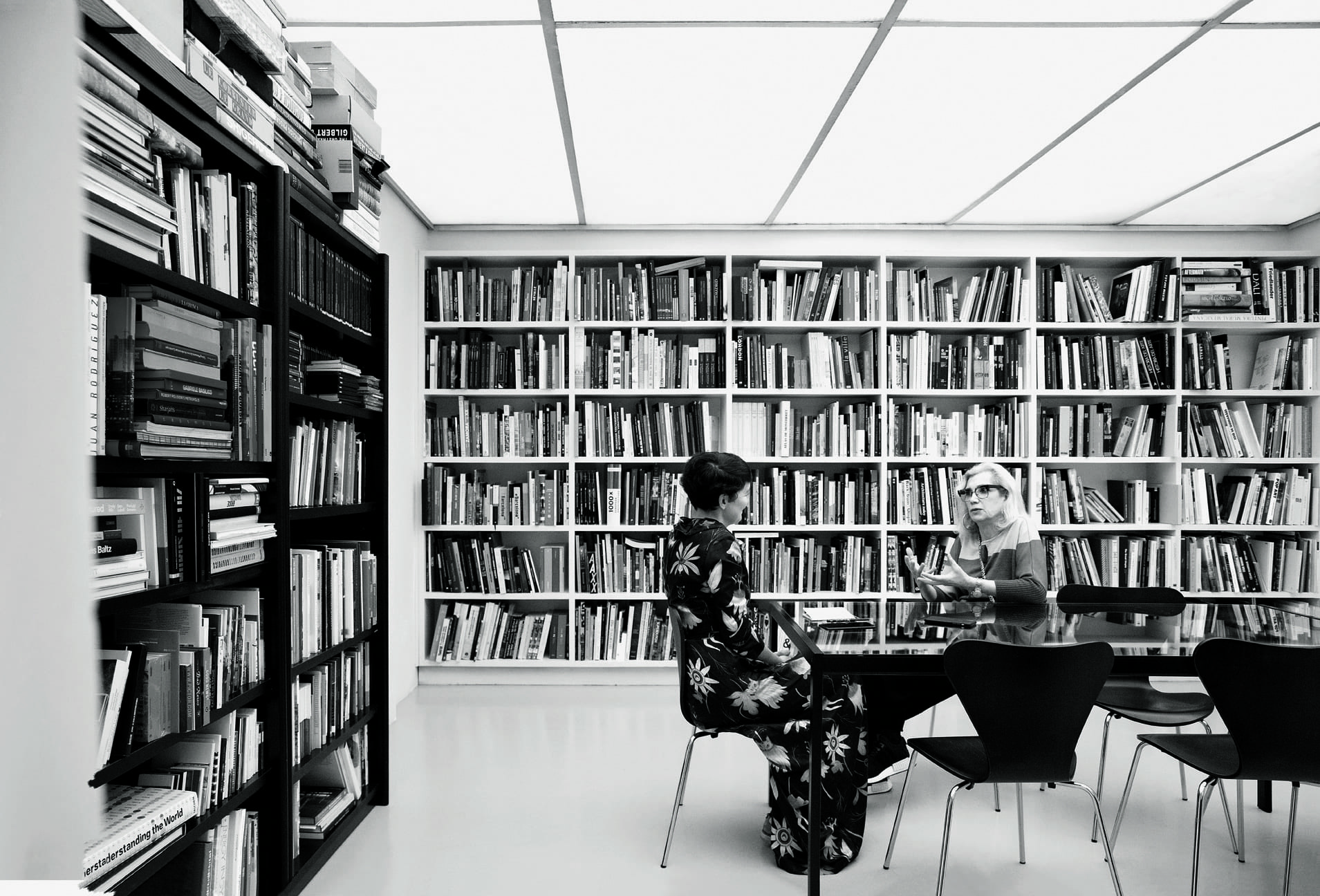

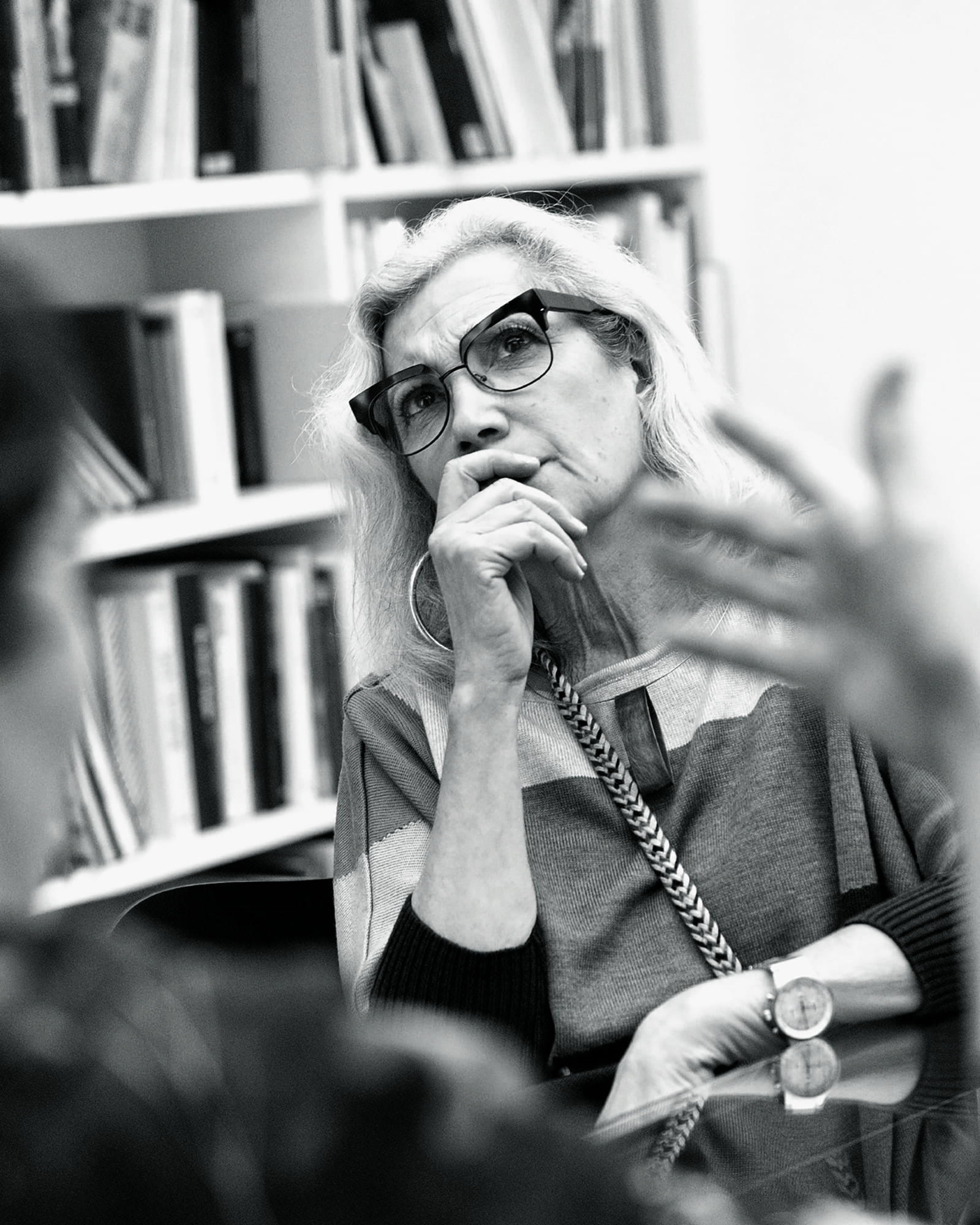

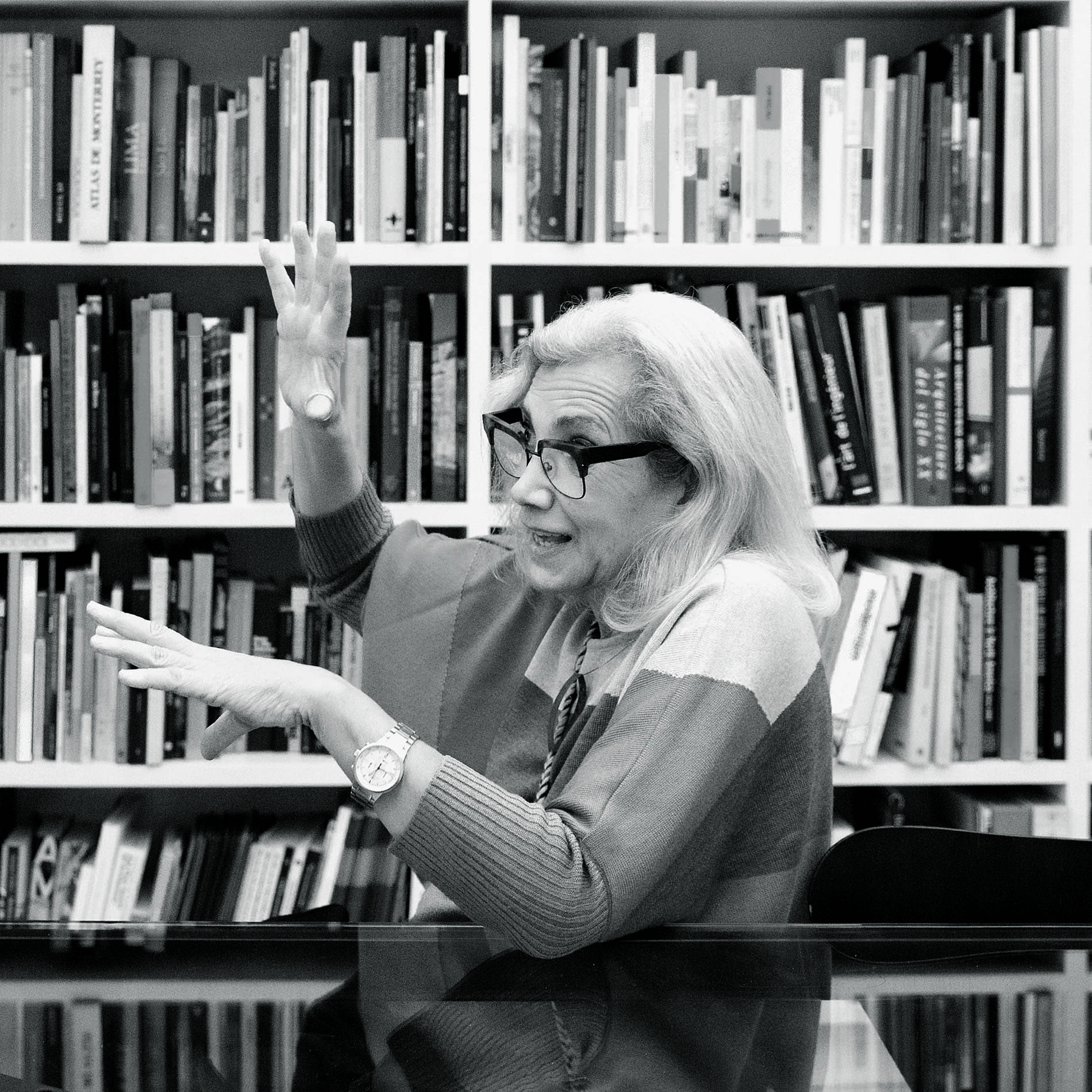

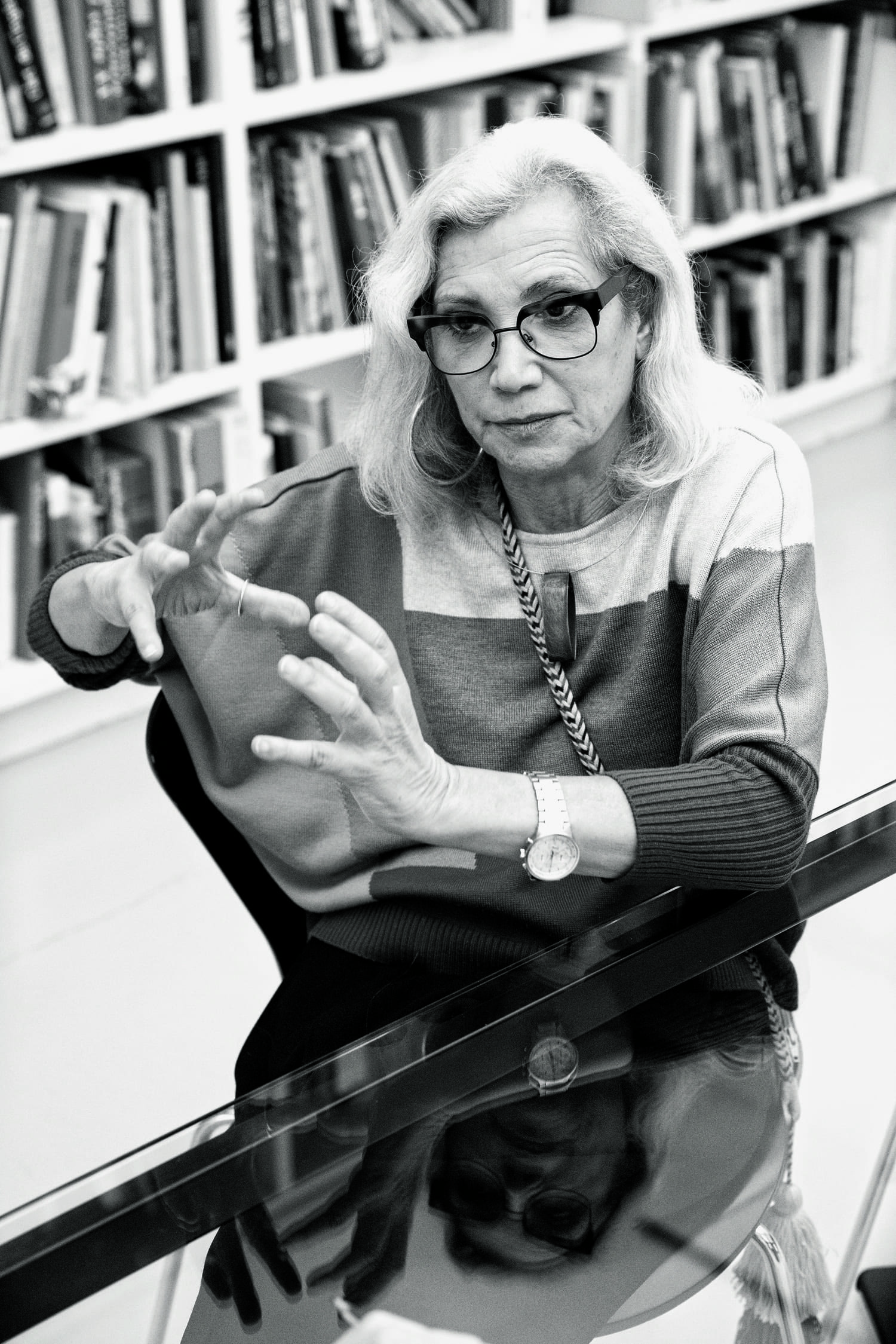

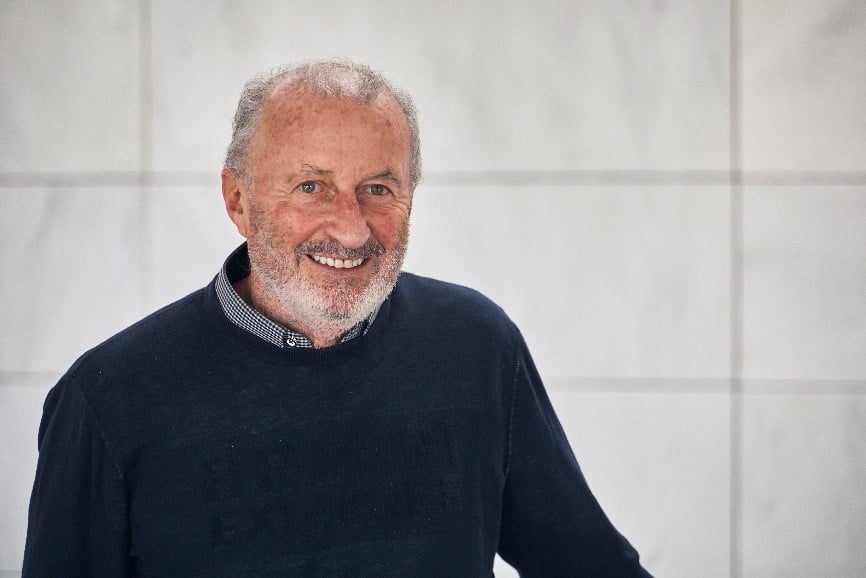

Von Vegesack & Schwartz-Clauss

Von Vegesack & Schwartz-Clauss

In dialogue

Varios

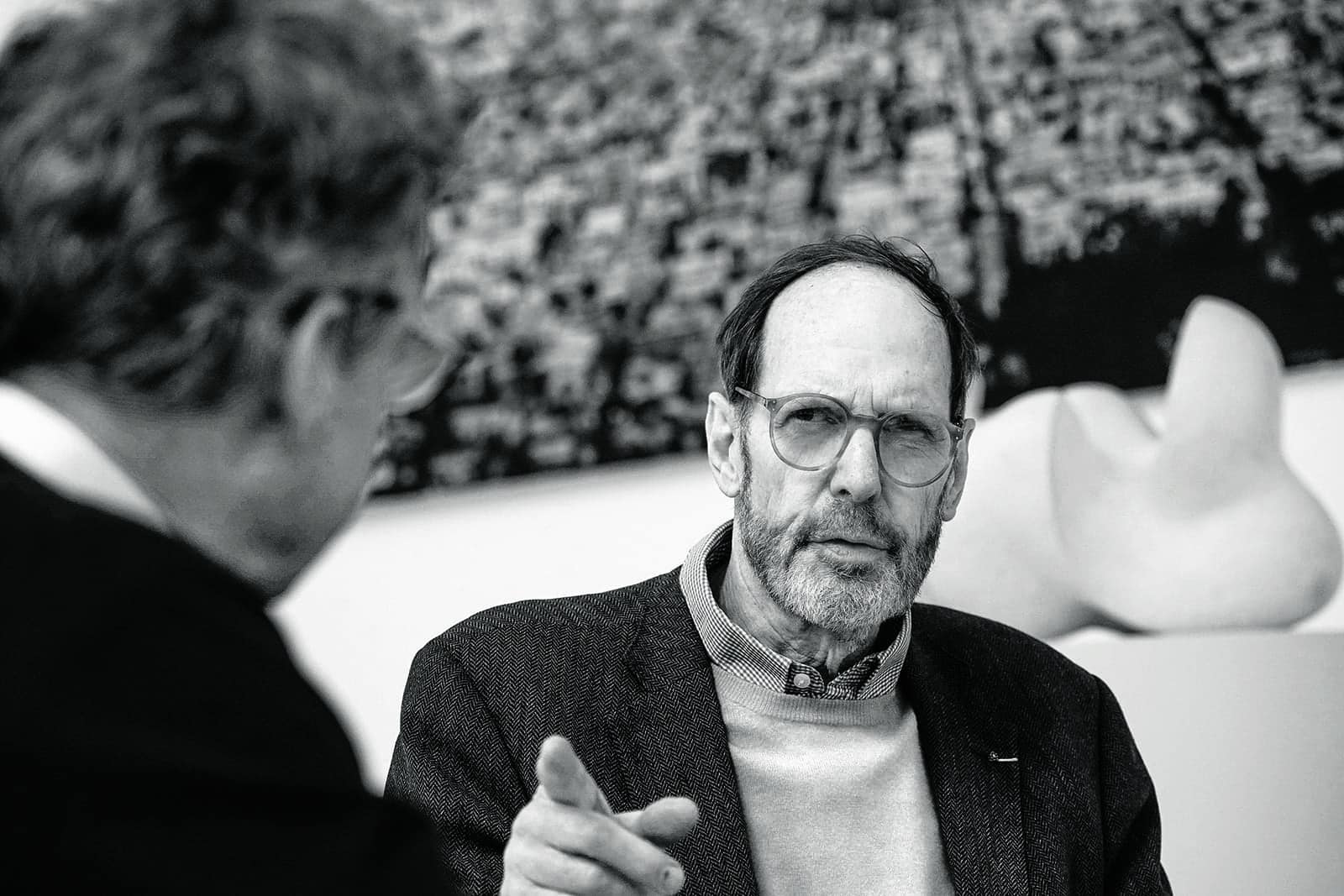

Alexander von Vegesack, fundador del Domaine de Boisbuchet, conversa con su actual director, Mathias Schwartz-Clauss, en la sede de la Norman Foster Foundation en Madrid.

Alexander von Vegesack nunca pensó en dedicarse al diseño, pero fue coleccionista desde pequeño. Fue el fundador del Vitra Design Museum, fabricante con el que trabajó durante gran parte de su trayectoria. Su vida, marcada por una infancia en la Alemania de posguerra, estuvo siempre relacionada con la convivencia y el trabajo en común, por lo que no es raro que todas sus ambiciones cristalizasen en el Domaine de Boisbuchet: un castillo en el sudoeste de Francia que reúne cada año a artistas, diseñadores y arquitectos en talleres multidisciplinares.

Estos talleres, reconocidos internacionalmente no sólo por los asistentes, sino por el alto nivel de sus ponentes, son sólo parte de una experiencia que incluye la estrecha convivencia y la íntima relación con la naturaleza. Mathias Schwartz-Clauss es el director de estos talleres desde 2013, y nos ayuda en estas líneas a trazar los orígenes de este ambicioso proyecto.

Mathias Schwartz-Clauss: Me gustaría empezar la conversación hablando del futuro en lugar del pasado. ¿Estás preocupado por tu legado? ¿Con lo que pueda pasar con Boisbuchet en 10 o 20 años? ¿Estás satisfecho con lo que hemos conseguido hasta el momento?

Alexander von Vegesack: Ni en el pasado ni en el futuro, prefiero pensar en el presente. Y lo que puedo hacer ahora para que Boisbuchet siga en el futuro. Pero lo que ocurrirá entonces ya está en manos de gente más joven, como tú mismo. Cambiará mucho y lo único que es constante en la vida es el cambio.

MSC: De acuerdo, pero si miras hacia el futuro y al mismo tiempo al pasado, desde tu infancia, ¿cuáles dirías que han sido los acontecimientos más importantes que te llevaron a este proyecto? Porque para mí, eso sería como un catálogo de tu trabajo.

AVV: Siempre he sido muy curioso. Y muy insistente con la gente que no me permitía indagar en las cosas que quería. Aprendí a perseguir mis intereses, y aunque no siempre tuve éxito (principalmente por razones económicas), aprendí de todo lo que hacía, y me expuse a muchas experiencias por las que la gente me juzgaba. Pero, si nos centramos en el periodo del Vitra Design Museum, diría que fue en mi época en Hamburgo donde más aprendí. Hacíamos teatro y muchos experimentos sociales que me ayudaron posteriormente en mis primeras exposiciones en Vitra. Diría por tanto que esa curiosidad constante es la que ha sido el hilo conductor de mi vida, y que todas las experiencias que derivan de ella han sido la base de lo que hoy hacemos.

«La curiosidad constante ha sido el hilo conductor de mi vida, y de ella deriva la base de lo que hoy hacemos»

MSC: Es interesante que menciones los experimentos sociales, me parece que la forma en la que vivías y trabajabas en la fábrica en Hamburgo se ha convertido en un aspecto importante de cómo estamos haciendo las cosas en Boisbuchet que, poco a poco se está convirtiendo en una comunidad.

AVV: Para mí, está muy relacionado con la comunidad que se forma en una pequeña familia o en un internado. Dieciséis personas en la misma habitación haciéndolo todo juntos creaban un sistema con el que me siento vinculado hasta hoy. Desde entonces todos los proyectos que han venido después los hice con amigos, viviendo juntos, trabajando juntos, asumiendo riesgos juntos…

MSC: En un momento de tu infancia también comienza el interés por los objetos. Entonces no eran cosas de diseño, la palabra diseño no existía en tu universo, pero ¿cómo describirías el desarrollo de esa admiración por los objetos hasta hoy?

AVV: Nací cuando a la guerra le quedaban dos meses, y vivíamos en Düsseldorf, rodeados de casas en ruinas. Como a todos los niños, nos gustaba colarnos en las ruinas a ver qué encontrábamos, como si fuésemos buscadores de oro. Una vez encontramos un mosaico en lo que había sido una iglesia, yo no sabía lo que eran los suelos de mosaico, pero me fascinaban esas pequeñas piezas. Formaba parte de esa curiosidad que me acompañó toda la vida.

MSC: Düsseldorf es un ejemplo de tu trabajo en general que es, a fin de cuentas, contar una historia a través de un objeto, contextualizándolo para crear una historia mayor. A veces inventas partes del relato para crear una nueva realidad a cada objeto.

AVV: Es verdad, pero es que no he terminado de contarte todo: años después fue a través de los mercados callejeros como seguí mi búsqueda de objetos. Podías encontrar cualquier cosa, y lo más interesante eran las historias que había detrás de cada una de ellas. Podías encontrar el mismo objeto 50 metros más abajo, y el tendero te contaría otra historia totalmente diferente. Continué haciendo esto en Holanda y luego en Francia… y siempre me interesó aprender no sólo del objeto, sino también de las personas que había detrás de ellos, quiénes eran y cómo hacían su negocio. Muchas veces se inventaban historias, pero siempre quedaba parte de realidad en el fondo. Así que creo que yo heredé parte de eso.

El coleccionismo en serio empezó, sin embargo, con las piezas de Thonet cuando necesitábamos muebles para el teatro. Recuerdo que encontré muchísimas cosas, algunas estropeadas, otras rotas… pero usábamos unas para reparar otras. Un día alguien nos contó cómo era la tecnología que se utilizaba, y quedé fascinado. Tanto que viajé a las fábricas de Checoslovaquia para aprender más. Entonces, como extranjero, estaba prohibido entrar en las fábricas, porque existía mucho espionaje industrial, pero finalmente lo conseguí, y obtuve muchos catálogos e información. Para acortar la historia, esto me llevó a hacer varias exposiciones, muchas de ellas en Estados Unidos. En uno de mis viajes allí leí que había fallecido William Wyler, y pensé que se trataba del cineasta Billy Wilder. Yo sabía que Billy Wilder tenía una gran colección de piezas de madera curvada, así que me puse en contacto con la familia para ver si podía comprar alguna de sus piezas.

«Siempre me interesó aprender no sólo de los objetos, sino también de las personas que había detrás de ellos»

MSC: Así que llamaste a la familia.

AVV: Así es, llamé y me cogió un hombre muy extrañado. Le di el pésame, le expliqué quién era y qué quería, pero pronto me interrumpió para decirme que él era Billy Wilder, y que no, no estaba muerto. Me preguntó si tenía papel y boli y me dictó una dirección para que acudiese. Fue así como nos conocimos y acabamos siendo buenos amigos. Una de las primeras cosas que hizo fue presentarme a Ray Eames, que me ayudó mucho en los principios de Boisbuchet porque, entre otras muchas cosas, fue la que me puso en contacto con Rolf Fehlbaum, director de Vitra, con quien trabajé durante muchos años.

MSC: Recuerdo que cuando nos conocimos, estabas trabajando en la creación del Vitra Design Museum, y yo, que aspiraba a ser un becario en el proyecto y que además no tenía ni idea de diseño, me quedé fascinado por la pasión con la que hablabas no sólo del futuro proyecto de Vitra, sino también de Boisbuchet, que entonces no era más que un montón de naves agrícolas. Pero tú, que eras especialista en crear colecciones para museos y organizar exposiciones, ¿en qué momento decidiste cambiar el enfoque hacia los talleres?

AVV: Está muy relacionado con mis orígenes. Siempre había querido continuar con el trabajo en grupo que había empezado en Hamburgo, y quería que esta experiencia, que dio forma a mi vida, pudiese vivirla mucha más gente. Así que aquí, de nuevo, volvemos a unir el pasado y el futuro.