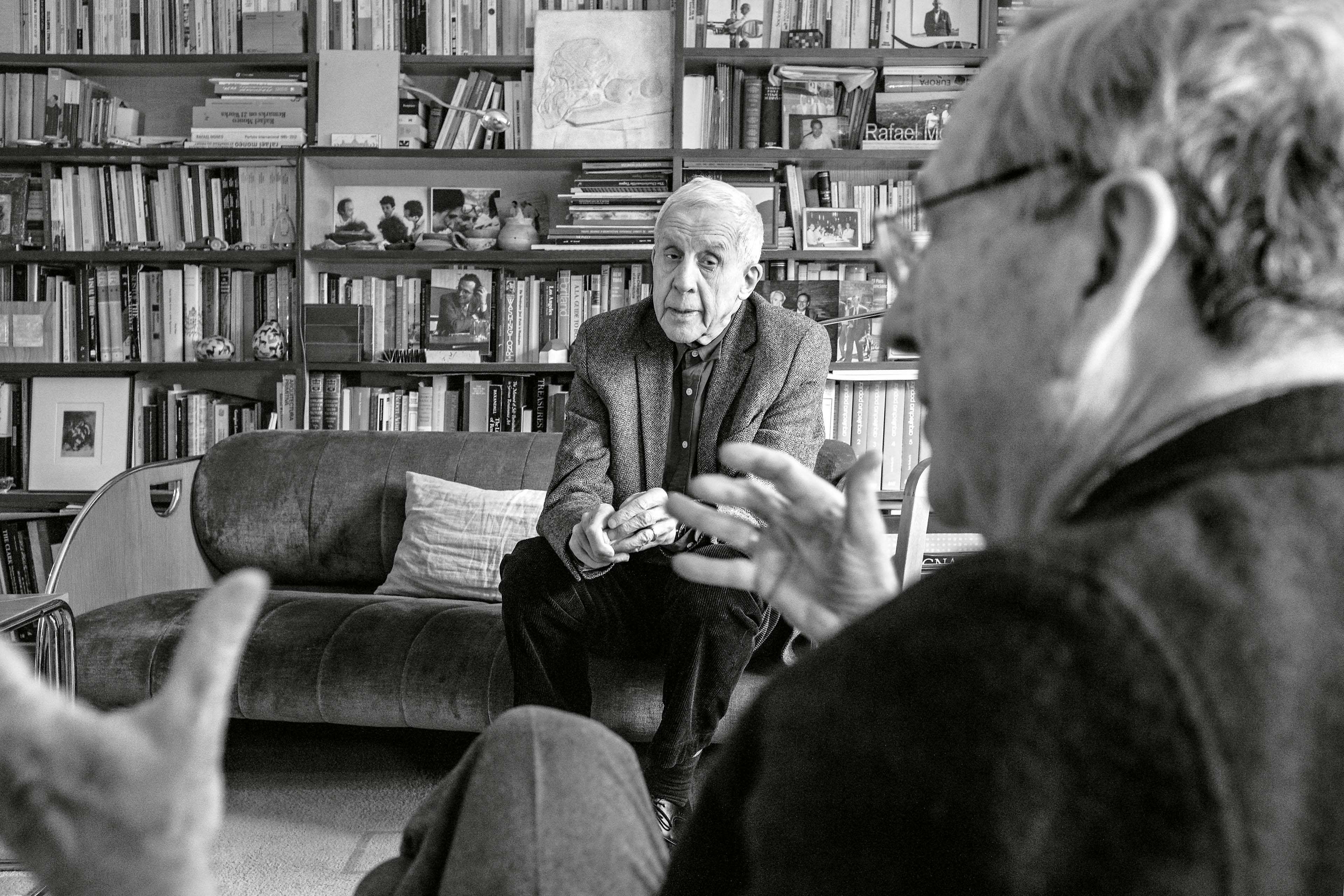

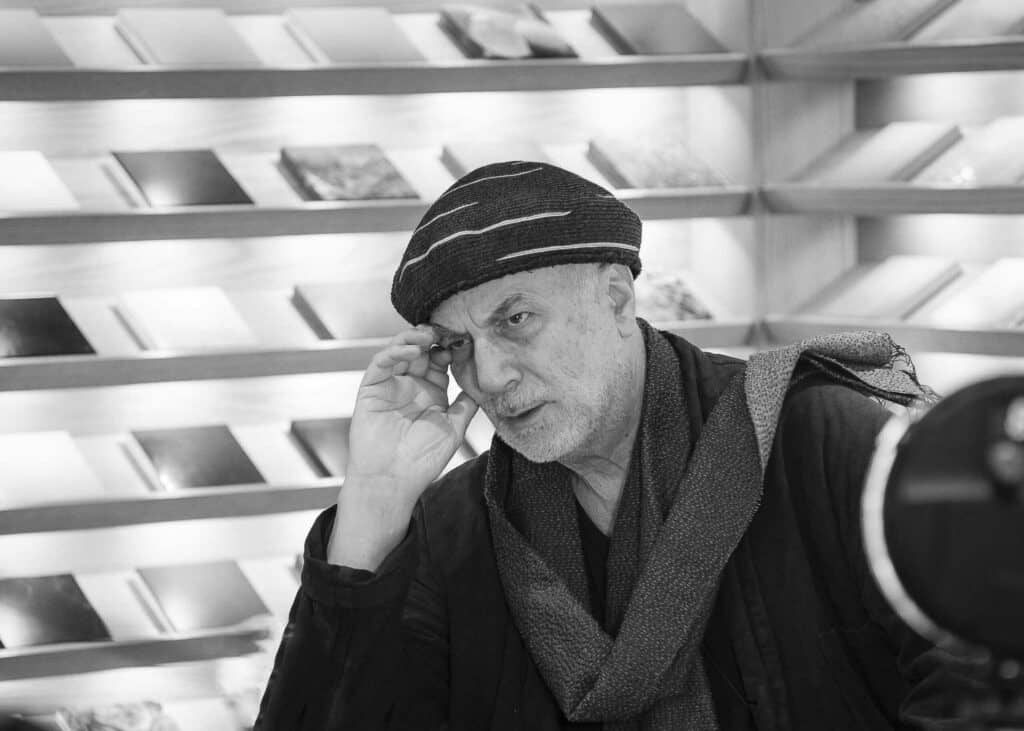

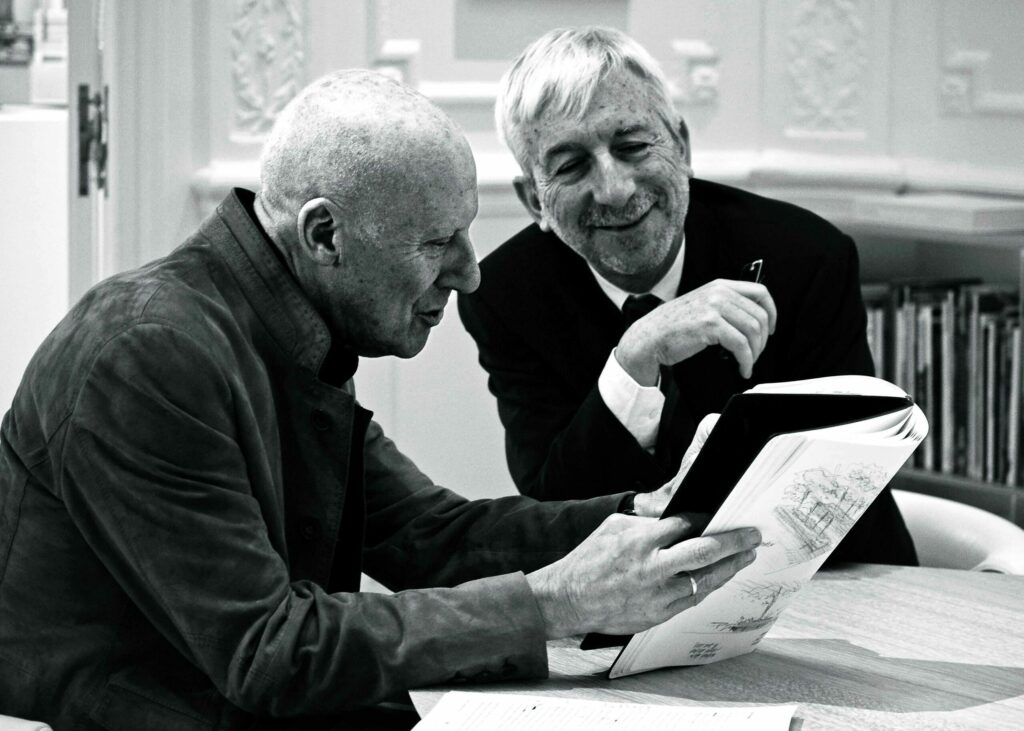

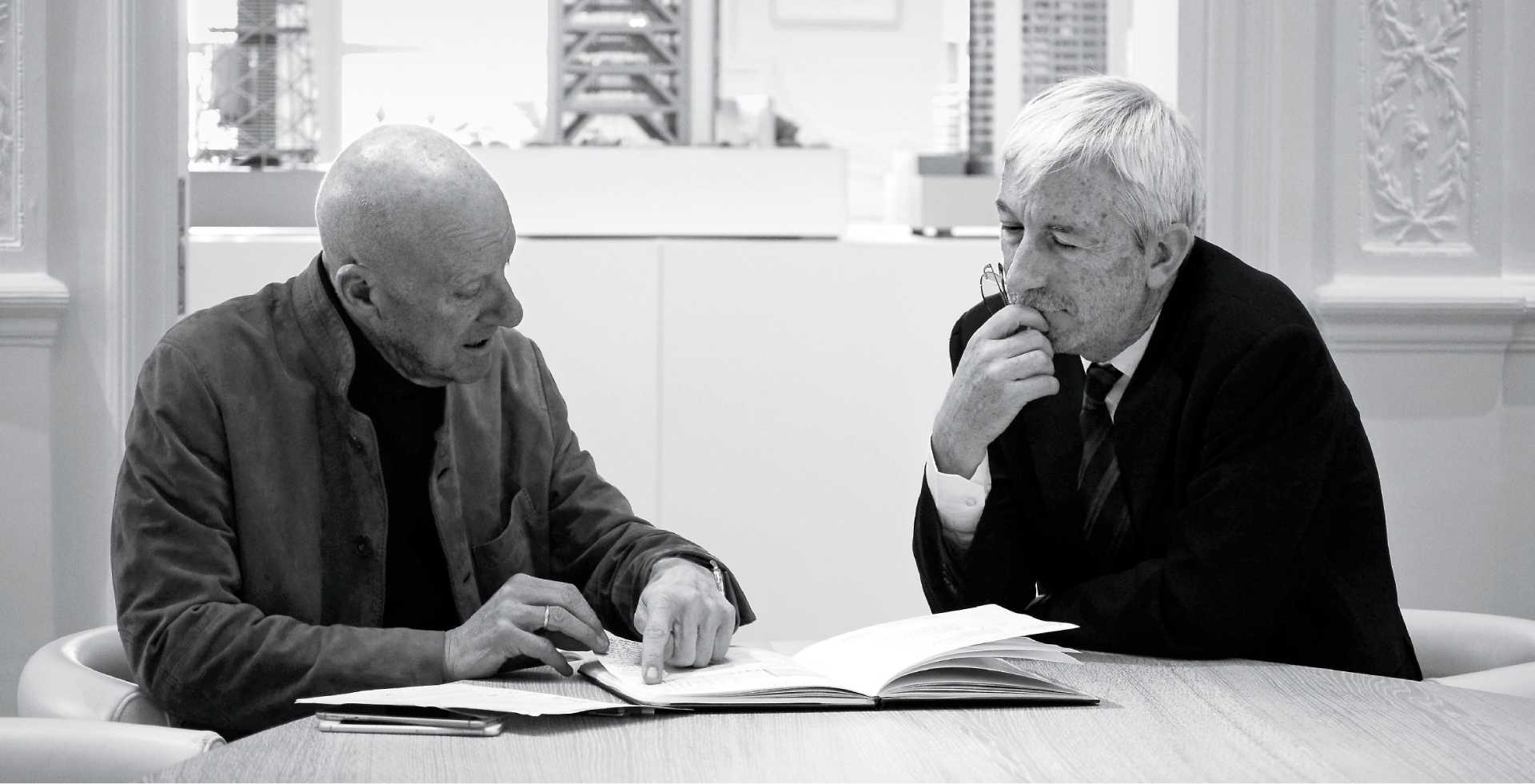

Souto de Moura & Pallasmaa

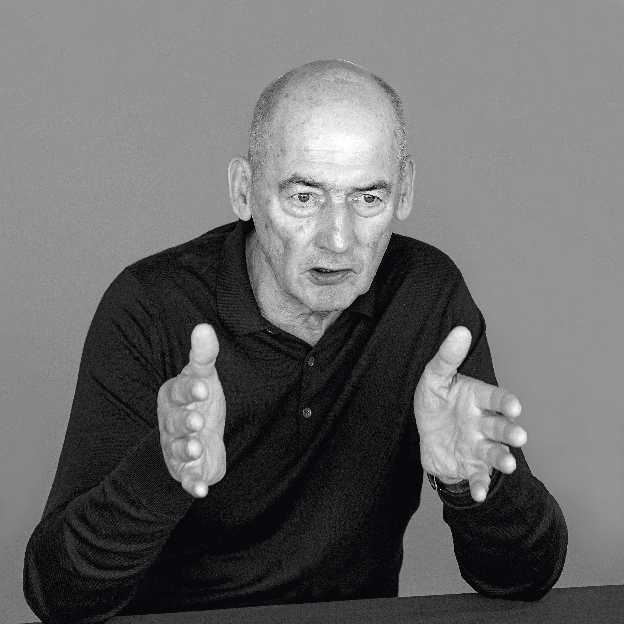

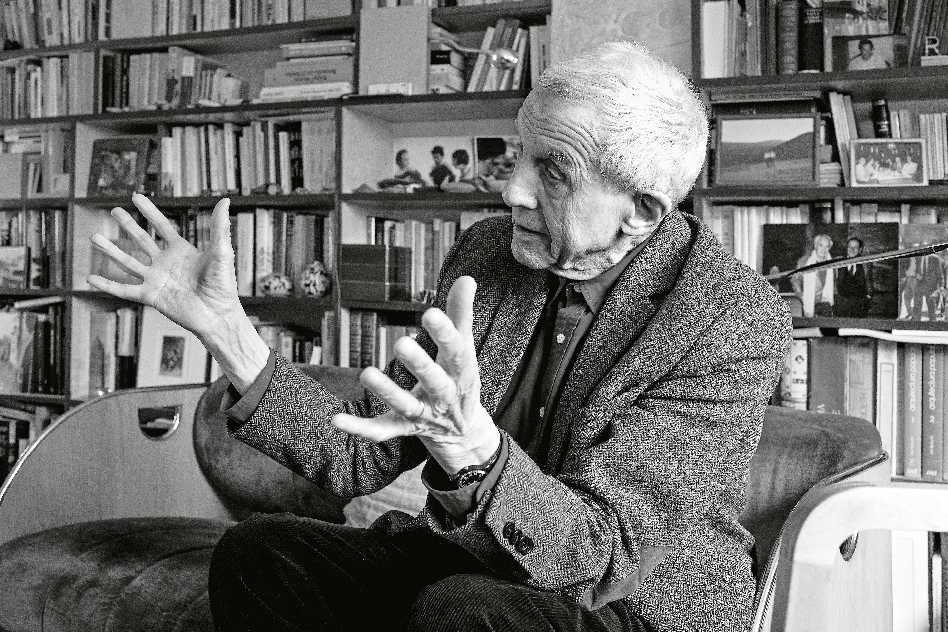

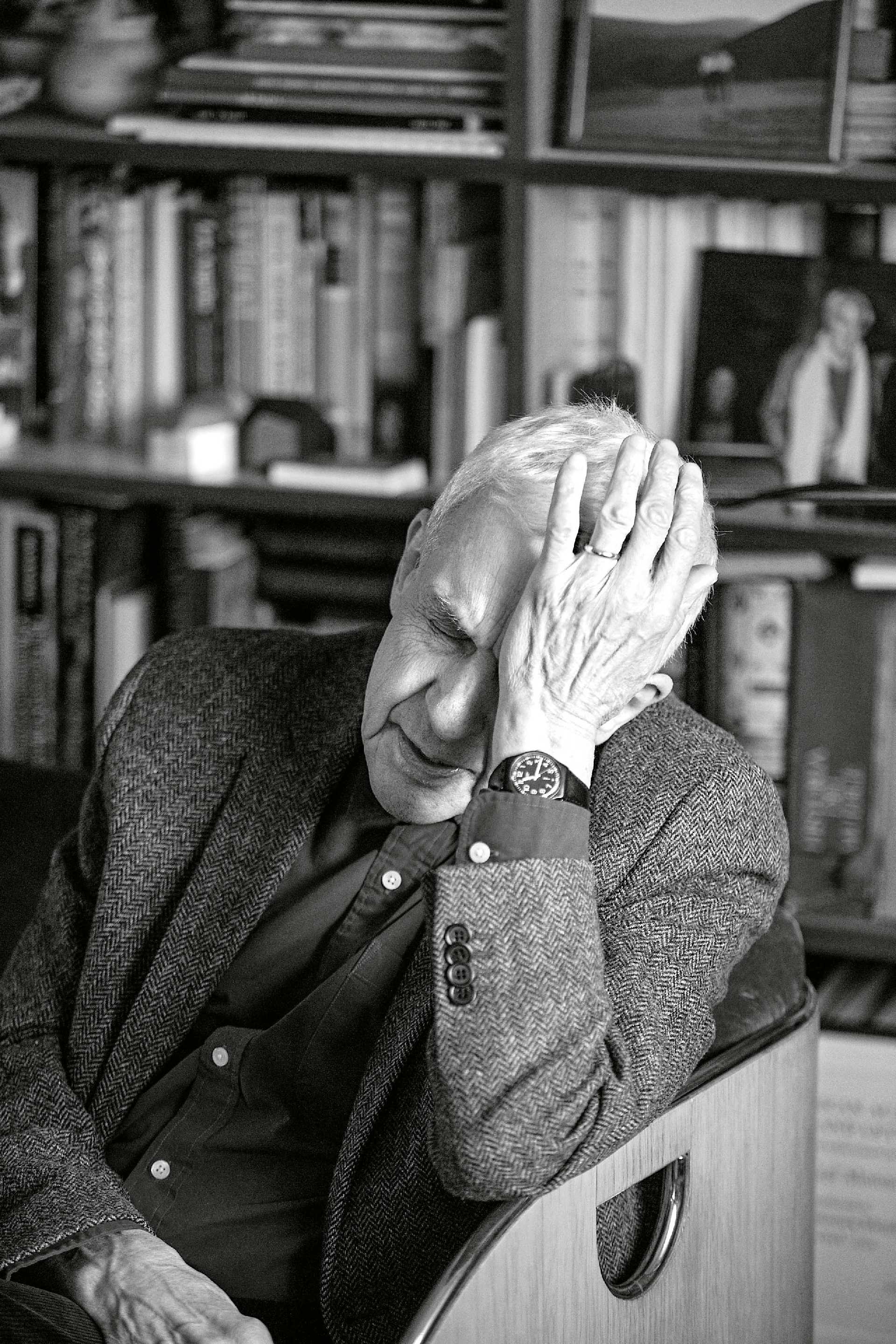

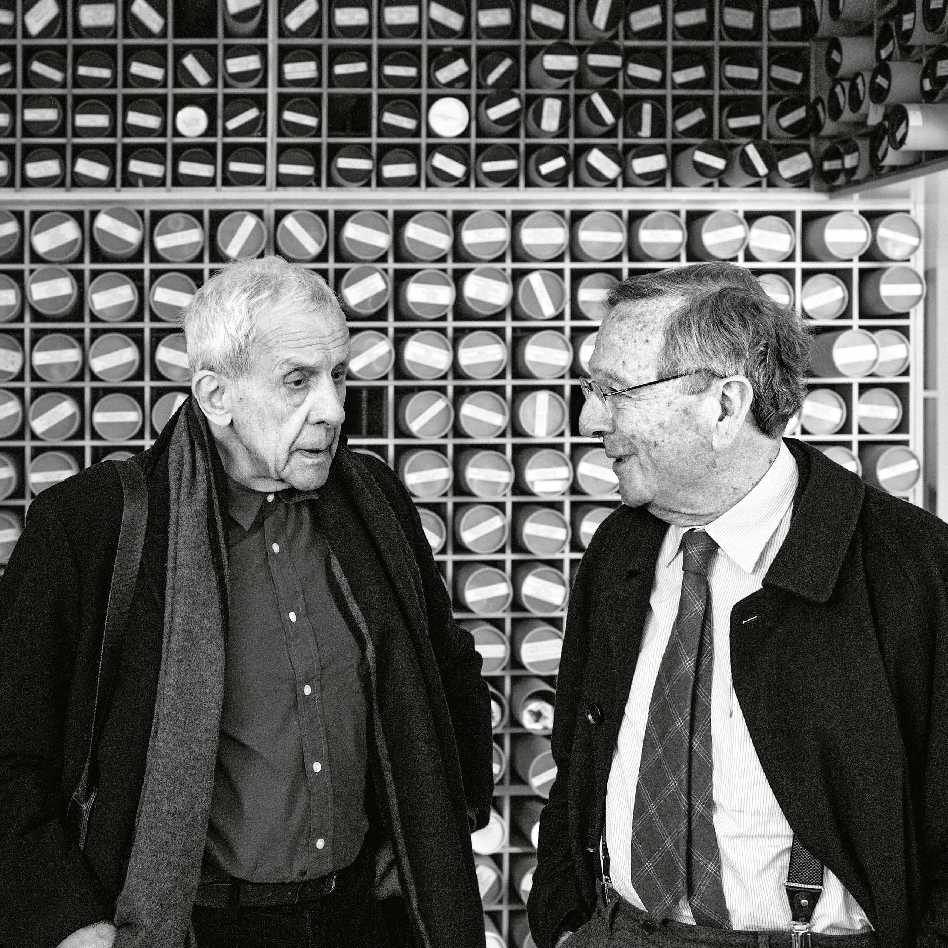

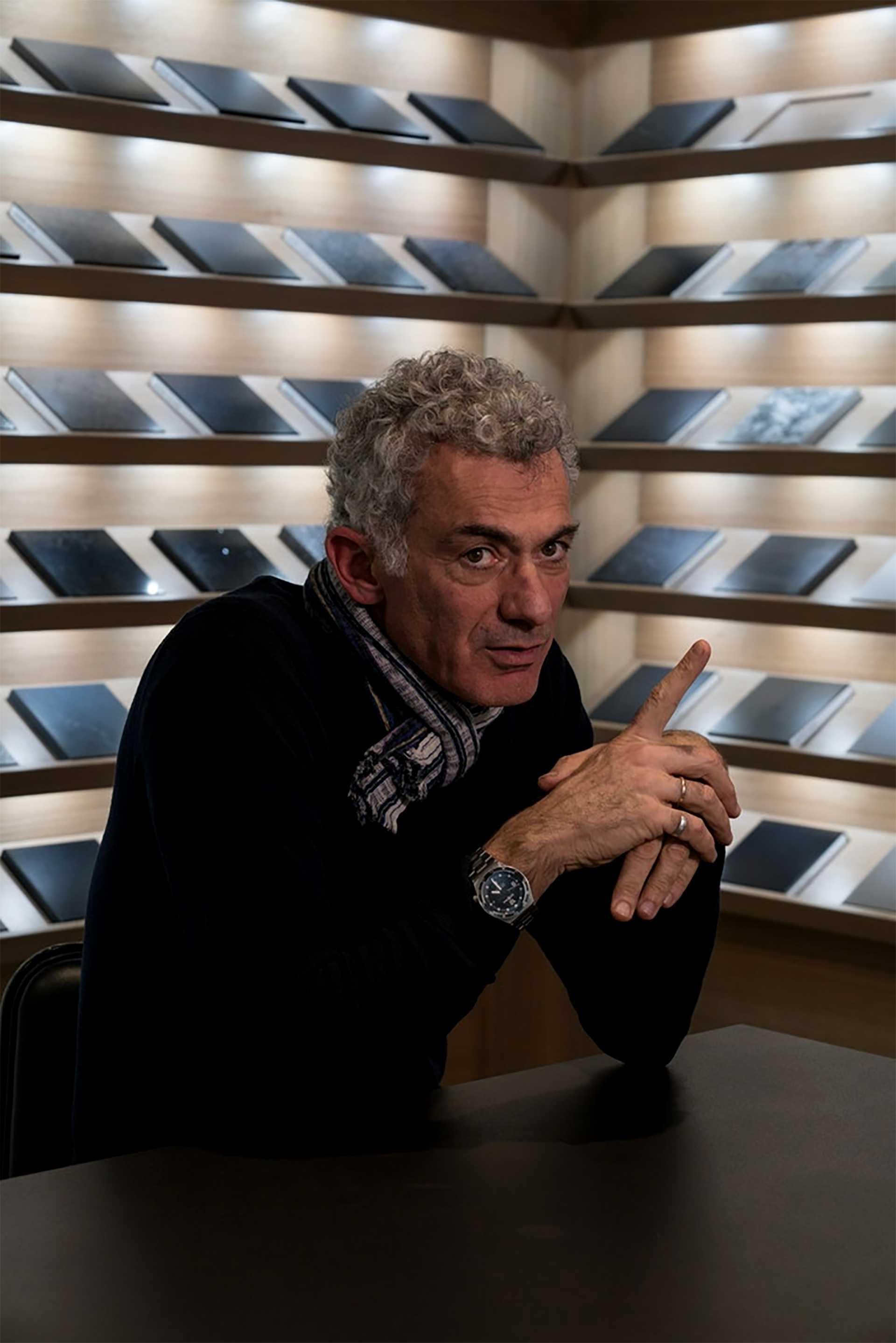

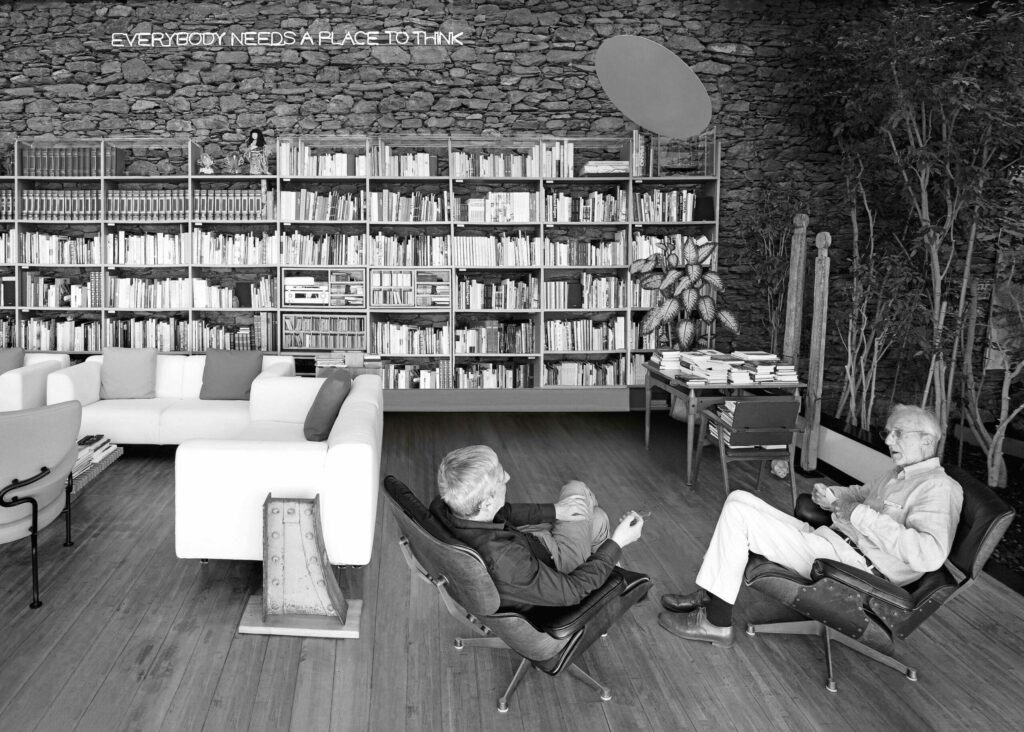

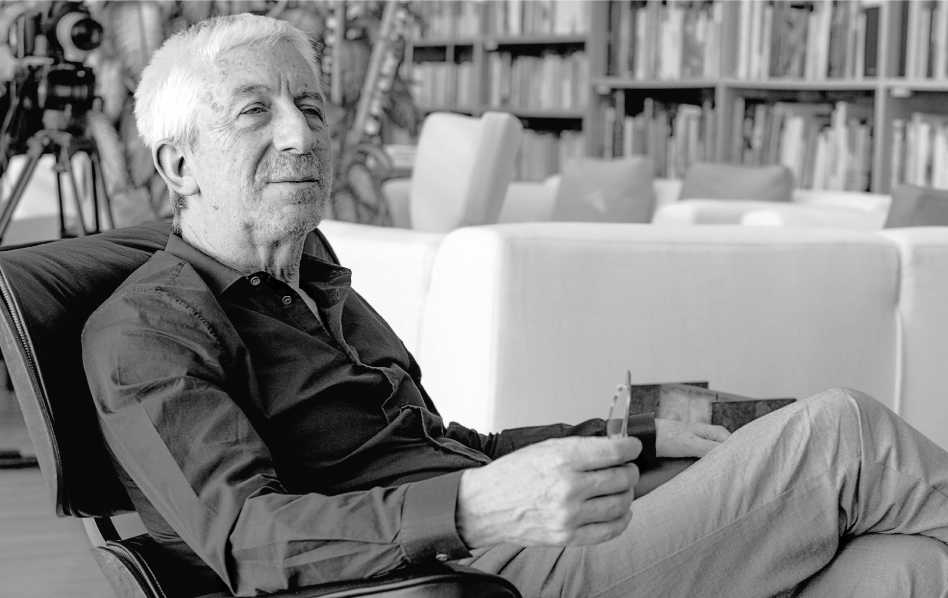

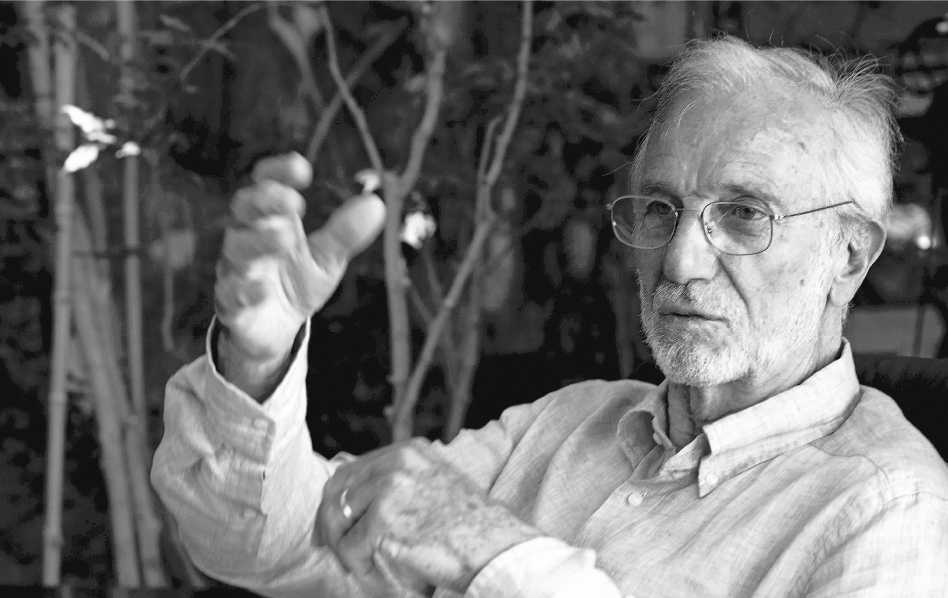

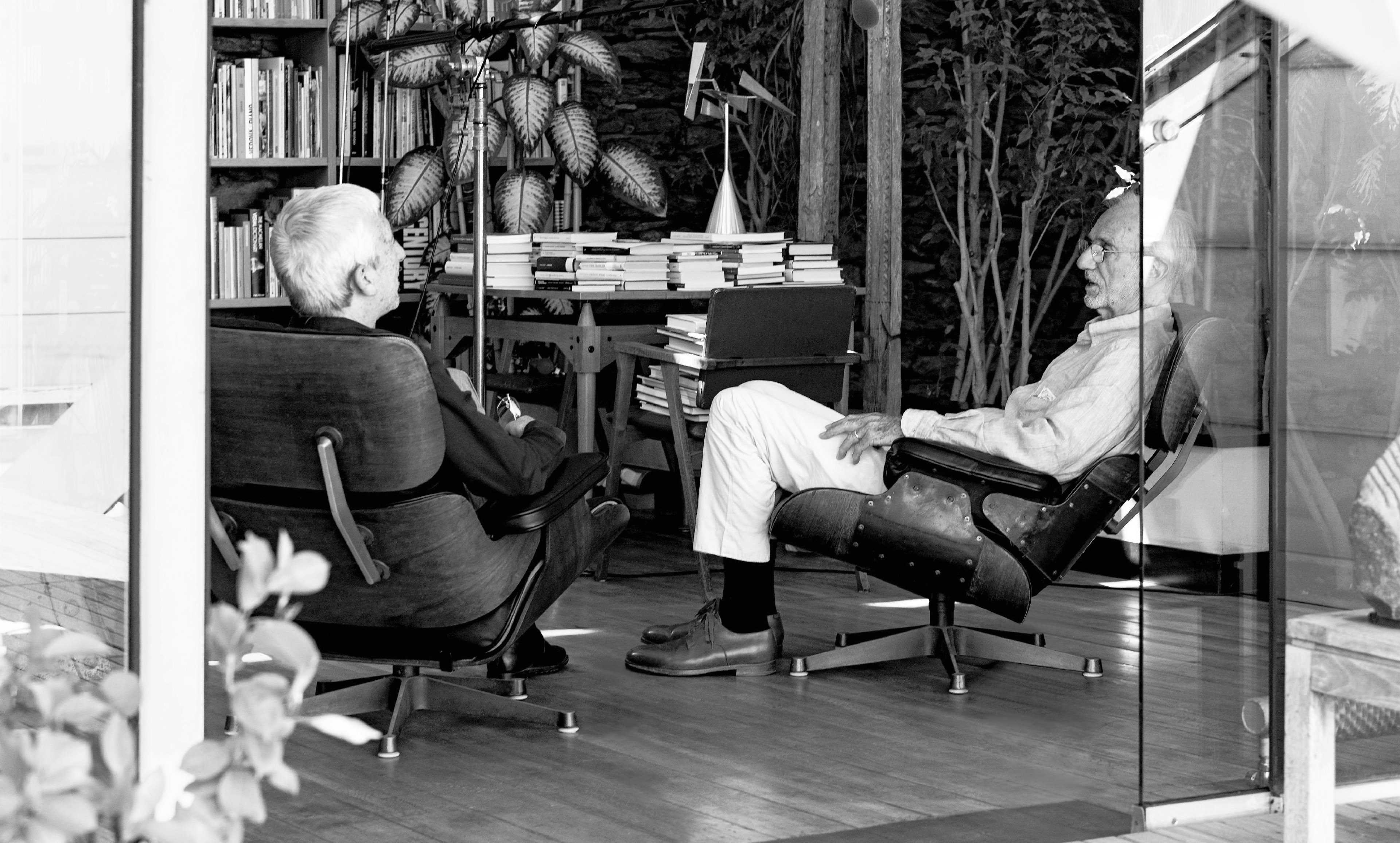

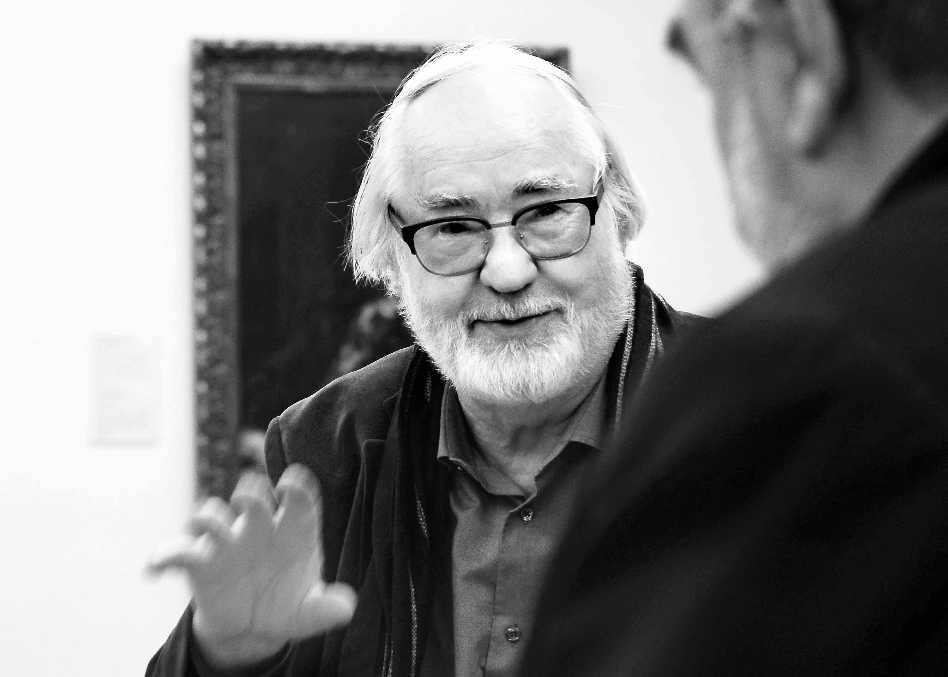

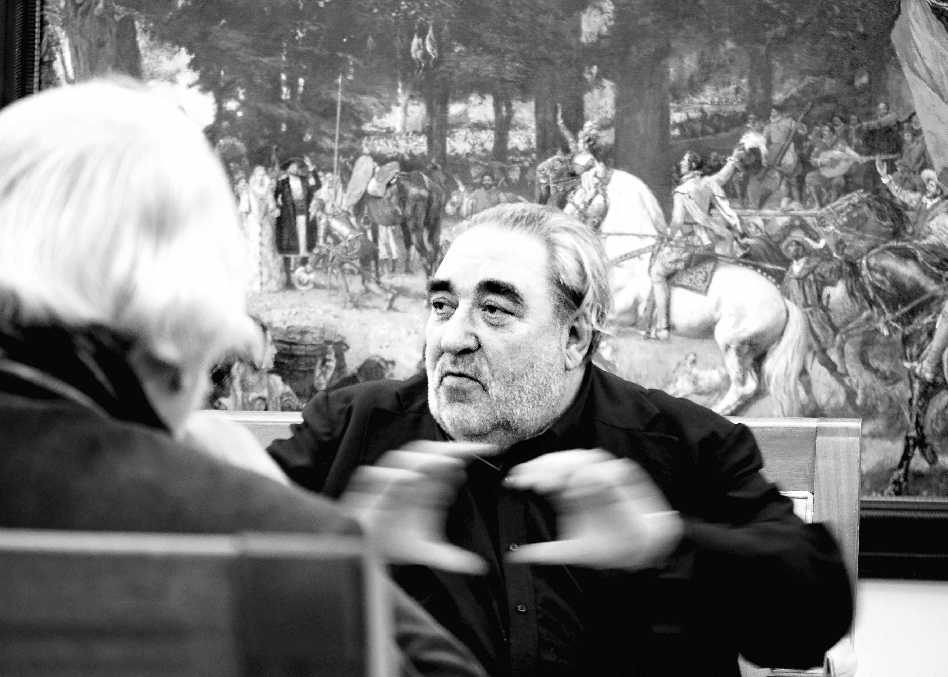

Eduardo Souto de Moura (Porto, Portugal, 1952), Pritzker Prize laureate of 2011, talks with the also architect and former dean at the Helsinki University of Technology, Juhani Pallasmaa (Hämeenlinna, Finland, 1936), about the influence of their countries in today’s architectural panorama.

Juhani Pallasmaa: We both come from countries that are considered the periphery of Europe. I have always felt that the peripheral condition is a very positive one, since one can observe from a critical distance and also with a certain delay. Which events would you say are changing this center versus periphery concepts in Europe and around the World?

Eduardo Souto de Moura: I was educated in this concept of periphery. I used to talk a lot with Siza about the culture of the local, and think that back then it was logical, but it is no longer so. Today, it is easier to get to Paris than to travel to some regions in my own country, like Évora. Basically because I have to go by car, and it takes me five hours instead of the two-hour plane to Paris. The concept of distance has changed. In architecture it is very similar. I remember one of my first projects, the Braga Market, where I designed a one-hundred-meter long concrete wall. The mayor told me then: “Eduardo, this is very expensive, can you do it cheaper, in stone, for example?” This anecdote is interesting because Jacques Herzog, who once heard me explain the project, was surprised about how rich Portugal was since we were building in stone in 1984, something impossible to imagine in Switzerland. In this model local stone is cheaper but, local wood, for example, costs double what it would cost in the north of Spain – I go to Vilagarcía de Arousa to buy American pine wood. Siza, like most of the architects from Porto, was very influenced by the work of Alvar Aalto because he defended the use of local materials. This idea created an anti avant-garde culture in the city, so this movement arrived later in Portugal, being as it is a peripheral country. Even so I am still quite skeptical about this concept of periphery.

JP: I think that this question of identity is very interesting and important. I have been travelling the world since I was very young – I am currently on my 86th trip around the globe – and the more I see, the more I feel my roots, the more I enjoy coming back home. Alvar Aalto made the point in a couple of interviews and essays, where he stated that local and universal are not opposites.

ESM: A Portuguese poet, Miguel Torga, used to say: “Universal is a house without walls.” I like this phrase. The distance between the local and the universal is very small. What I liked about Le Corbusier is that he found a universal language, the universal house. But it was also always local, all his architecture comes from the vernacular. _x005F_x000D_

JP: I agree with you. At the same time, however, it is important to see the way we are mixing cultures, rather violently, not only in Europe but also around the world. And I think that this question of identity and background history has become very important and complex.

ESM: We have to rebuild the geography. You can move ideas around, but the physical landscape does not change. I cannot make the same building in Chicago and in Lisbon.

JP: Exactly. You cannot change the climate, for example. When I was young, I did not pay any attention to these things, but with age I have come to understand more and more that I am a product of a local situation. I personally have had the fortune of travelling around the world and knowing the world, but I have realized that I see it from a very distinct point in southern Finland.

ESM: When I started working as an architect, I was afraid of windows. When I had to design a window, I panicked. It is the most difficult thing you can do in architecture. Opening a negative in a wall is very complicated.

JP: Also, the window is the most powerful way of connecting your building with the landscape. That brings us back to this idea of place. Merleau-Ponty has an interesting argument when he says that we do not come to see the work of art, but the world according to the work of art. And I think that is the essence of architecture, what a window reveals.

ESM: Perhaps that’s why, like a Matisse painting, they are so difficult to design. Last week we won a competition for a theater where we reused a facade of a disciple of Perret, with vertical windows and an elegant proportion. I liked the idea of having a conflict between Perret and Le Corbusier, with horizontal and vertical windows, so I proposed both kinds of windows in the same part of the building. Finally they advised me not to use horizontal windows, which surprised me because it was such an authoritarian ban in the 21st century. _x005F_x000D_

JP: That makes me think that as a real architect you have to reinvent the window every time.

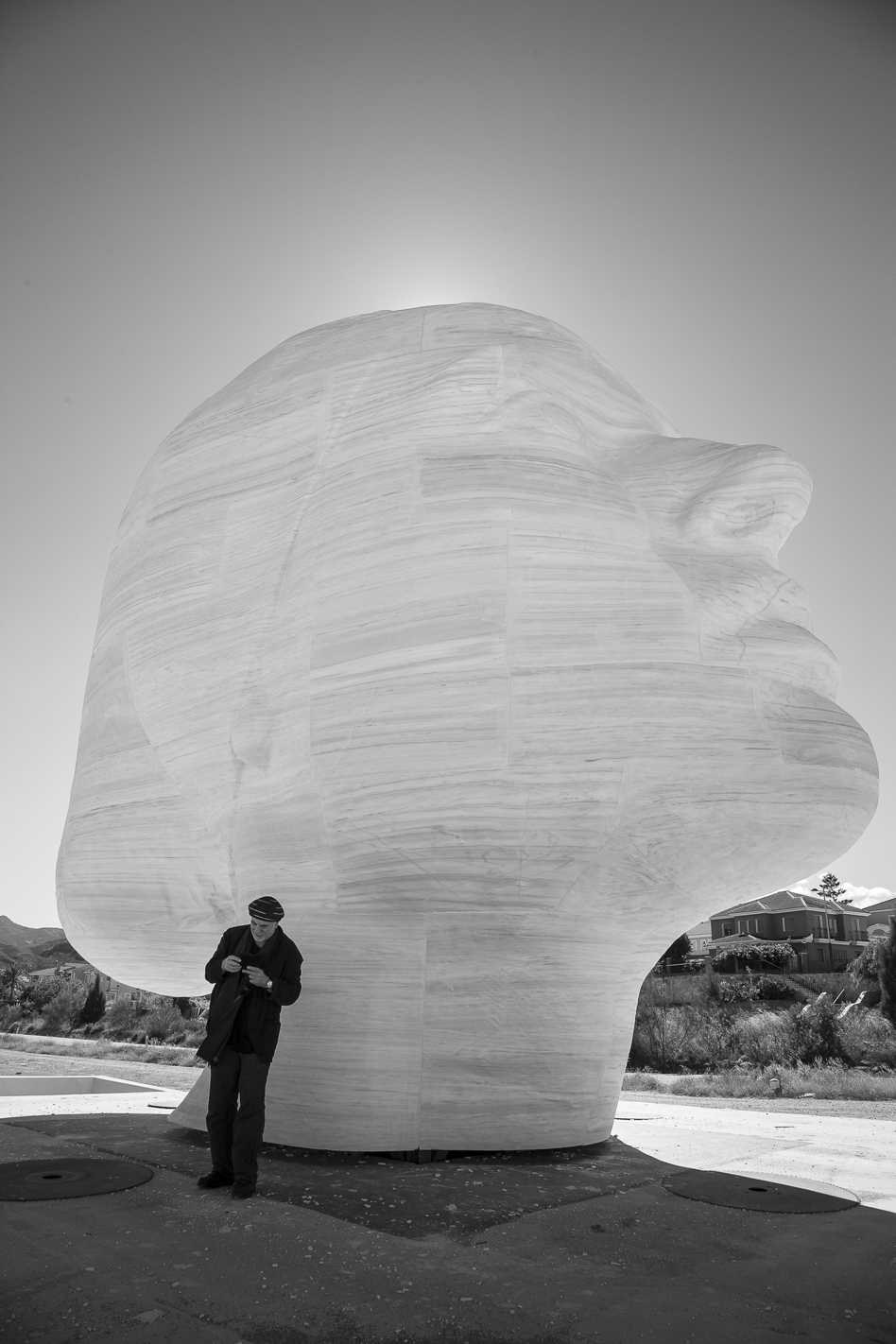

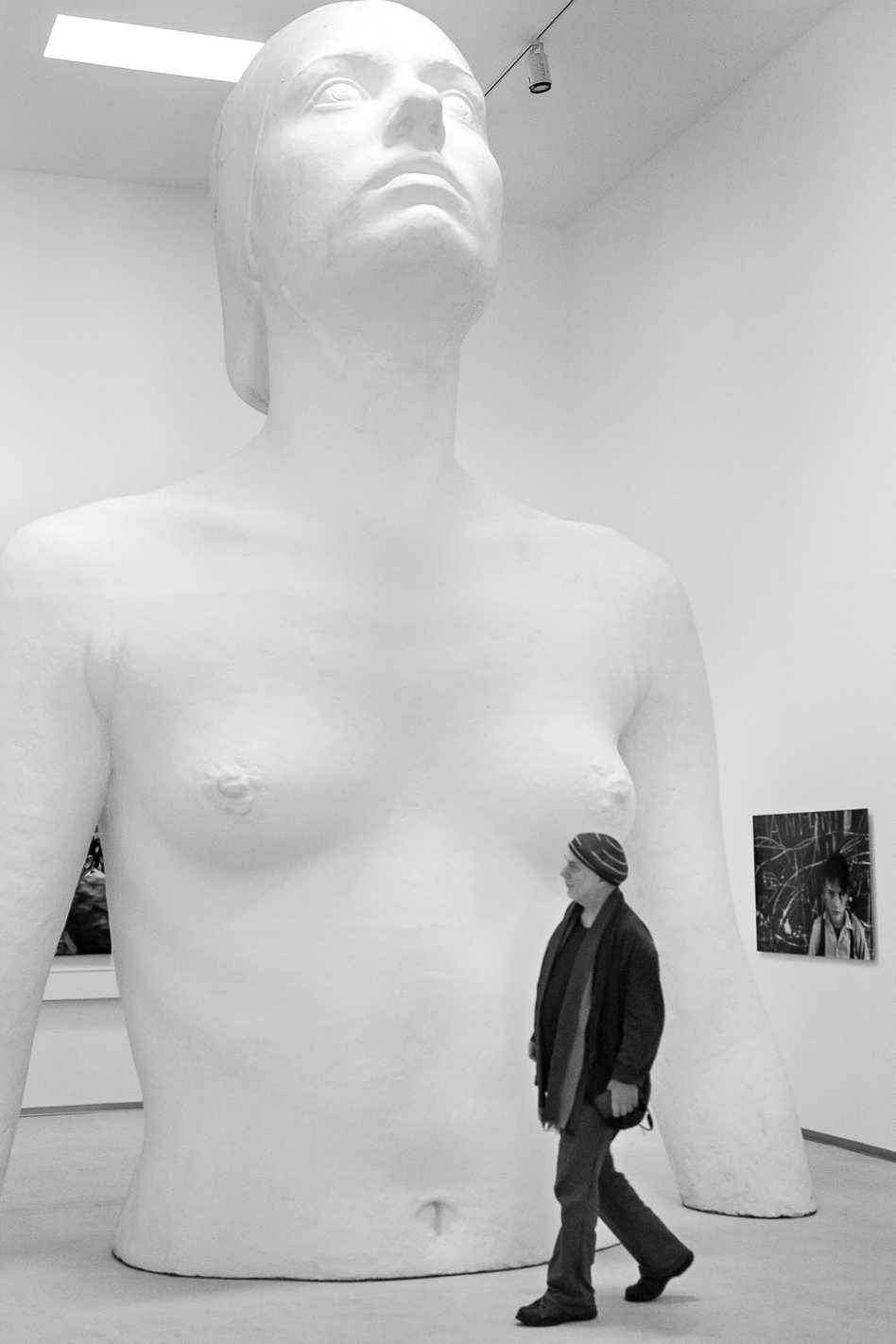

ESM: That’s right. And it is dramatic for me… I think that Siza or Moneo, in the morning, after brushing their teeth, design a window. Just like that. They are naturals. When Siza and I designed the Portuguese pavilion in Hannover, the pavilion was built with a cork facade, a very abstract curved roof, a big wall, and a kitchen behind. Once, visiting it with Siza, I told him: “Alvaro, there is a big problem because the firemen say we have to open a security door in the wall.” It was a big wall, very abstract, like a sculpture, and the door would make it very domestic. Siza then designed a door in five minutes, and that is how it was done later. I kept looking at the door using my hand to blind it, and I realized it was actually better with the door. It became a real window, which had to do with life, not the gesture of an artist’s installation.

JP: For me a window is the eye of the building, and the door is the mouth. They are essential to the physiognomy of the body, of the building. In my own design I have never been able to understand the door as a given thing. I always start with the question of what the door is. There is always a distinct context and a purpose for the door, and every door is fundamentally different.

ESM: That is the real problem of architecture. When I was in Paris, I had lots of discussions with Aldo Rossi about the windows. He would tell me: “Eduardo, you always have to think about the practical issues: from the inside to the outside, from the outside to the inside.” It is like designing a portrait.

JP: You began your career in Porto and now you work in many parts of the world. Do you feel comfortable working abroad?

ESM: I am very grateful to be working in many countries, and it would not be right to say that I do not like it, but I do prefer to work in Porto. For me, the most important thing for an architect today is to have time. To have time to think, to change, to make models, do sketches, go to the construction site on a Saturday morning when nobody is there, take pictures… I think it is like gastronomy: you cannot go there in a rush. You have to enjoy it quietly. This is why the quality of architecture today is poor, because time is money, and clients ask for short deadlines, which is normal, the problem is that architects accept this. _x005F_x000D_

JP: Sigfried Giedion, in Space, Time and Architecture, talks about how Finland is with Alvar Aalto, the same way that Spain is with Picasso, or Ireland with James Joyce. How strongly are you doing your work from a Portuguese perspective?

ESM: What I like most about Portugal is the atmosphere, the mood. Architecture is not only physical. If you design a chair, you can do it alone in one week, but designing something in a place, in a country, involves thinking about many other things. That is the reason why architecture is a social matter. To obtain a high quality in architecture you have to think about time, material, craftsmen, a good relation with the client… There is no good building with a bad client. _x005F_x000D_

JP: When I was in Doha teaching, I could not think of designing anything there, because I would not know where to start. In my experience it is a city that has no place at all. It is just a limitless placelessness.

ESM: The car and the hotel. But this matter of the regional and the local is very interesting. I talked about it with Frampton, who always defends regionalism. I think it is a bit ridiculous right now to talk about regionalism as it was understood before, today there is a new regionalism. Pachi Mangado, for instance, comes often to Portugal because he is very interested in Portuguese crafts, and he comes to discuss this thing or the other with the craftsmen. It is a team. And I feel more identified with this kind of work than the one they develop in Lisbon, for instance. It is not a question of rivalry, but of empathy.

JP: I feel the same, since Finland has the tradition of not talking. In my observation, in Finland the quality of architecture is better when there is a crisis (economic, political, or social) and it goes down when there is a period of wealth, when everything is taken for granted. I don’t think architecture can exist without the belief that there is a future. Architecture is grounded on hope.

ESM: When people ask me, “Eduardo, what would you say to young architects in this time of crisis?” I say that I have always worked in a time of crisis. It is good to represent an opposition to crisis. In Chinese, crisis has two meanings: change and project. It is always positive. You must be careful also, because there is a lot of opportunism. Clients, for instance, always try to reduce budgets and so on…